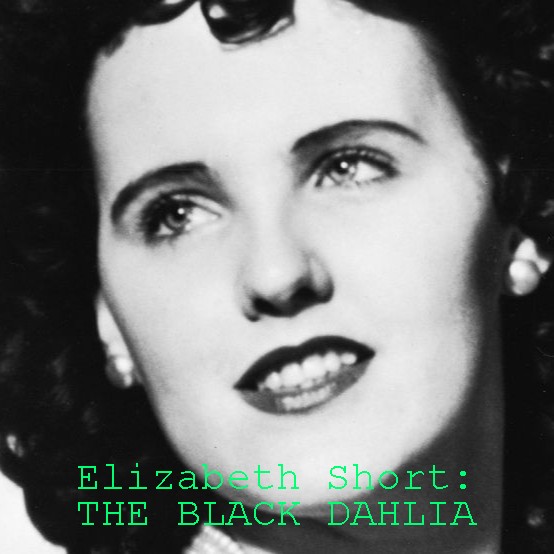

The Case of THE BLACK DAHLIA Revisited

The Black Dahlia

The 1947 murder of a 22-year-old Hollywood hopeful in Los Angeles has never been solved.

On the morning of January 15, 1947, a mother taking her child for a walk in a Los Angeles neighborhood stumbled upon a gruesome sight: the body of a young naked woman sliced clean in half at the waist.

The body was just a few feet from the sidewalk and posed in such a way that the mother reportedly thought it was a mannequin at first glance.

Despite the extensive mutilation and cuts on the body, there wasn’t a drop of blood at the scene, indicating that the young woman had been killed elsewhere.

The ensuing investigation was led by the L.A. Police Department. The FBI was asked to help, and it quickly identified the body—just 56 minutes, in fact, after getting blurred fingerprints via “Soundphoto” (a primitive fax machine used by news services) from Los Angeles.

The young woman turned out to be a 22-year-old Hollywood hopeful named Elizabeth Short—later dubbed the “Black Dahlia” by the press for her rumored penchant for sheer black clothes and for the Blue Dahlia movie out at that time.

Short’s prints actually appeared twice in the FBI’s massive collection (more than 100 million were on file at the time).

First, she had applied for a job as a clerk at the commissary of the Army’s Camp Cooke in California in January 1943.

Second, she had been arrested by the Santa Barbara police for underage drinking seven months later. The Bureau also had her “mug shot” in its files and provided it to the press.

In support of L.A. police, the FBI ran records checks on potential suspects and conducted interviews across the nation.

Based on early suspicions that the murderer may have had skills in dissection because the body was so cleanly cut, agents were also asked to check out a group of students at the University of Southern California Medical School.

And, in a tantalizing potential break in the case, the Bureau searched for a match to fingerprints found on an anonymous letter that may have been sent to authorities by the killer, but the prints weren’t in FBI files.

Who killed the Black Dahlia and why? It’s a mystery.

The murderer has never been found, and given how much time has passed, probably never will be.

The legend grows…

The 22-year-old Short had been sliced in two at the waist and completely drained of blood. Some of her organs — such as her intestines — had been removed and neatly placed underneath her buttocks.

Pieces of flesh had been cut away from her thighs and breasts. And her stomach was full of feces, leading some to believe that she’d been forced to eat them before she was killed.

The most chilling mutilations, however, were the lacerations on her face. The killer had sliced each side of her face from the corners of her mouth to her ears, creating what’s known as a “Glasgow smile.”

Since the body had already been washed clean, Los Angeles Police Department detectives concluded that she must have been killed elsewhere before being dumped in Leimert Park.

Near her body, detectives noted a heel print and a cement sack with traces of blood that had presumably been used to transport her body to the vacant lot.

The LAPD reached out to the FBI to help identify the body by searching their fingerprint database. Short’s fingerprints turned up rather quickly because she had applied for a job as a clerk at the commissary of the U.S. Army’s Camp Cooke in California back in 1943.

And then her prints turned up a second time since she had been arrested by the Santa Barbara Police Department for underage drinking — just seven months after she’d applied to the job.

The FBI also had her mugshot from her arrest, which they provided to the press. Before long, the media began reporting every salacious detail they could find about Short.

Meanwhile, Elizabeth Short’s mother Phoebe Short didn’t learn of her daughter’s death until reporters from The Los Angeles Examiner telephoned her pretending that Elizabeth had won a beauty contest.

They pumped her for all the details they could get on Elizabeth before revealing the terrible truth. Her daughter had been murdered, and her corpse had been dismembered in unspeakable ways.

As the media learned more about Elizabeth Short’s history, they began to brand her as a sexual deviant. One police report read, “This victim knew at least fifty men at the time of her death and at least twenty-five men had been seen with her in the sixty days preceding her death… She was known as a teaser of men.”

They gave Short the nickname, “The Black Dahlia,” due to her reported preference for wearing a lot of sheer black clothing. This was a reference to the movie The Blue Dahlia, which was out at the time. Some people spread the false rumor that Short was a prostitute, while others baselessly claimed that she liked to tease men because she was a lesbian.

Adding to her mystique, Short was reportedly a Hollywood hopeful. She had moved to Los Angeles just six months before her death and worked as a waitress. Sadly, she had no known acting jobs and her death became her one claim to fame.

But as famous as the case was, authorities had tremendous difficulty figuring out who was behind it. However, members of the media did receive a few clues.

On January 21st, about a week after the body was found, the Examiner received a call from a person claiming to be the murderer, who said he would be sending Short’s belongings in the mail as proof of his claim.

Shortly thereafter on the 24th, the Examiner received a package with Short’s birth certificate, photos, business cards, and an address book with the name Mark Hansen on the cover. Also included was a letter pasted together from newspaper and magazine letter clippings that read, “Los Angeles Examiner and other Los Angeles papers here is Dahlia’s belongings letter to follow.”

All of these items had been wiped down with gasoline, leaving no fingerprints behind. Though a partial fingerprint was found on the envelope, it was damaged in transport and never analyzed.

On January 26th, another letter arrived. This handwritten note read, “Here it is. Turning in Wed. January 29, 10 a.m. Had my fun at police. Black Dahlia Avenger.” The letter included a location. Police waited at the appointed time and place, but the author never showed.

Afterward, the alleged killer sent a note made of letters cut and pasted from magazines to the Examiner that said, “Have changed my mind. You would not give me a square deal. Dahlia killing was justified.”

Yet again, everything sent by the person had been wiped clean with gasoline, so investigators couldn’t lift any fingerprints from the evidence.

At one point, the LAPD had 750 investigators on the case and interviewed more than 150 potential suspects linked to the Black Dahlia killing. Officers heard more than 60 confessions during the initial investigation, but none of them were considered legitimate. Since then, there have been more than 500 confessions, none of which led to anyone being charged.

As time went on and the case went cold, many people assumed that the Black Dahlia murder was a date gone wrong, or that Short had run into a sinister stranger late at night while walking alone.

After over 70 years, the Black Dahlia murder case remains open. But in recent years, a couple of intriguing — and chilling — theories have emerged.

The Man Who Thinks His Father Killed Elizabeth Short

Shortly after his father’s death in 1999, now-retired LAPD detective Steve Hodel was going through his dad’s belongings when he noticed two photos of a woman who bore a striking resemblance to Elizabeth Short.

After discovering these haunting images, Hodel began using the skills he had gained as a policeman to investigate his own deceased father.

Hodel went through newspaper archives and witness interviews from the case, and even filed a Freedom of Information Act to obtain FBI files on the Black Dahlia murder.

He also had a handwriting expert compare samples of his father’s writing to the writing on some of the notes sent to the press from the alleged killer. The analysis found a strong possibility that his father’s handwriting matched, but the results were not conclusive.

On the grislier side, the Black Dahlia crime scene photos showed that Short’s body had been cut in a manner consistent with a hemicorporectomy, a medical procedure that slices the body beneath the lumbar spine. Hodel’s father had been a doctor — who attended medical school when this procedure was being taught in the 1930s.

Additionally, Hodel searched his father’s archives at UCLA, finding a folder full of receipts for contracting work on his childhood home.

In that folder, there was a receipt dated a few days before the murder for a large bag of concrete, the same size, and brand as a concrete bag found near Elizabeth Short’s body.

By the time Hodel began his investigation, many of the police officers who originally worked on the case were already dead. However, he carefully reconstructed conversations these officers had about the case.

Eventually, Hodel compiled all of his evidence into a 2003 bestseller called Black Dahlia Avenger: The True Story.

While fact-checking the book, Los Angeles Times columnist Steve Lopez requested official police files from the case and made an important discovery. Shortly after the murder, the LAPD had six main suspects, and George Hodel was on their list.

In fact, he was such a serious suspect that his home was bugged in 1950 so the police could monitor his activities. Much of the audio was innocuous, but one chilling exchange stuck out:

“8:25pm. ‘Woman screamed. Woman screamed again. (It should be noted, the woman not heard before the scream.)'”

Later that day, George Hodel was overheard telling someone, “Realize there was nothing I could do, put a pillow over her head and cover her with a blanket. Get a taxi. Expired 12:59. They thought there was something fishy. Anyway, now they may have figured it out. Killed her.”

He continued, “Supposin’ I did kill the Black Dahlia. They couldn’t prove it now. They can’t talk to my secretary anymore because she’s dead.”

Even after this shocking revelation, which seems to support that George Hodel killed Short — and possibly also his secretary — the Black Dahlia case still hasn’t been officially closed. However, this hasn’t stopped Steve Hodel from investigating his father.

He says he has found details from dozens of other murders that could possibly be connected to his father, implicating him not only as the Black Dahlia murderer but also as a deranged serial killer.

Hodel’s research has even garnered some attention from law enforcement. In 2004, Stephen R. Kay, the head deputy for L.A. County’s district attorney office, said that if George Hodel was still alive he would have enough to indict him for the Elizabeth Short murder.

Did Leslie Dillon Murder The Black Dahlia?

In 2017, British author Piu Eatwell announced that she had finally solved the decades-old case, and published her findings in a book called Black Dahlia, Red Rose: The Crime, Corruption, and Cover-Up of America’s Greatest Unsolved Murder.

The real culprit, she claimed, was Leslie Dillon, a man who police briefly considered the primary suspect but ultimately let go. However, she also claimed there was much more to the case besides the killer himself.

According to Eatwell, Dillon, who worked as a bellhop, murdered Short at the behest of Mark Hansen, a local nightclub and movie theater owner who worked with Dillon.

Hansen was another suspect that had eventually been let go — and the owner of the address book that had been mailed to the Examiner. He later claimed that he gave the address book to Short as a gift.

Short had reportedly stayed with Hansen a few nights, and he was one of the last people reported to have spoken with her before her death in a phone call on January 8th. Eatwell alleges that Hansen was infatuated with Short and came onto her, though she rebuffed his advances.

Then, he supposedly called on Leslie Dillon to “take care of her.” Hansen, it seemed, knew Dillon was capable of murder but didn’t realize just how deranged he really was.

Previously, Leslie Dillon had worked as a mortician’s assistant, where he could have potentially learned how to bleed a body dry.

Eatwell also discovered, from police records, that Dillon knew details about the crime that had not yet been released to the public. One detail was that Short had a tattoo of a rose on her thigh, which had been cut out and shoved inside her vagina.

For his part, Dillon claimed to be an aspiring crime writer and told authorities that he was writing a book about the Dahlia case — which never materialized.

Despite all the evidence pointing to him, Dillon was never charged with the crime. Eatwell claims he was released due to Mark Hansen’s ties to some of the cops at the LAPD. While Eatwell believes the department was corrupt to begin with, she also thinks that Hansen contributed largely to its corruption by exploiting his ties to certain officers.

Another discovery that lent itself to Eatwell’s theory was a crime scene found at a local motel. During her research, Eatwell came across a report by Aster Motel owner Henry Hoffman. The Aster Motel was a small, 10-cabin facility near the University of Southern California.

On the morning of January 15, 1947, he opened the door to one of his cabins and found the room “covered in blood and fecal matter.” In another cabin, he discovered that someone had left a bundle of women’s clothes wrapped up in brown paper, which was also stained with blood.

Instead of reporting the crime, Hoffman simply cleaned it up. He had been arrested four days earlier for beating his wife and didn’t want to risk another run-in with the police.

Eatwell believes that the motel is where Elizabeth Short was murdered. Eyewitness reports, though uncorroborated, claim that a woman who resembled Short was seen at the motel shortly before the murder.

Eatwell’s theories have not been proven, as everyone involved with the original Black Dahlia murder case is most likely dead by now, and many official LAPD documents remain locked away in vaults.

However, Eatwell remains confident in her findings, and truly believes that she’s solved the mysterious and gruesome case of the Black Dahlia murder.

Though we still don’t know for certain who killed the Black Dahlia, these recent theories present compelling cases. And it’s possible that the truth is still out there, just waiting for the right investigation to finally bring it to light.

Sign in

Sign in Sign in

Sign in Sign in

Sign in