Welcome to the 34 Circe Salon.

Welcome to Make Matriarchy Great Again. All right.Oh, welcome.Welcome, everyone, to the 34 Searcy podcast.I'm Dawn Sam Alden and I am here with John Marlon Newcomb.Fabulous.And we have as our guest today, Sally Roche Wagner.

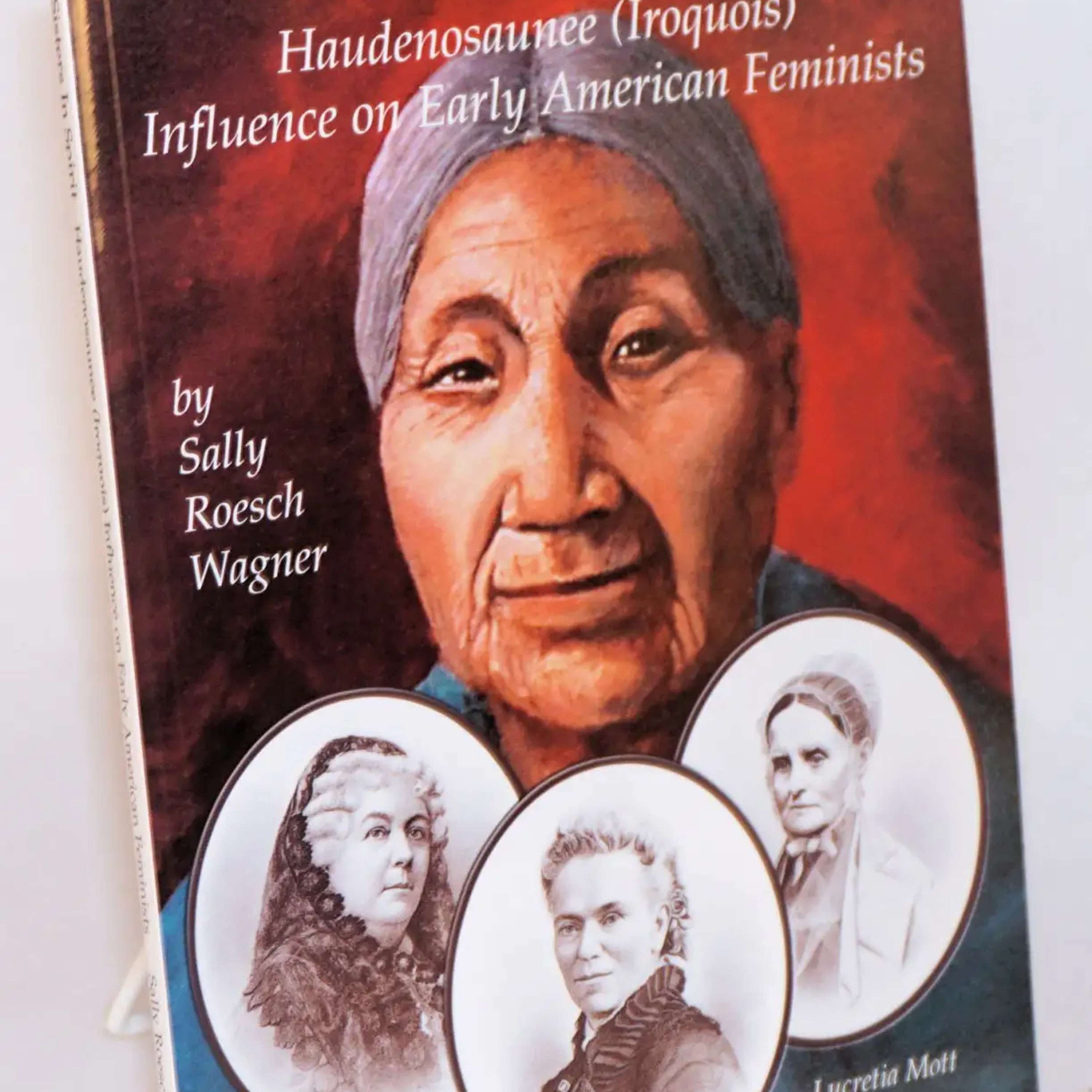

And you, Sally, have written a variety of books, but the one that we are probably going to be talking about most closely today is your book Sisters in Spirit, which is the Haudenosaunee or Iroquois, as they're sometimes known, influence on early American feminists.

We, Sean and I have been talking for many years about that connection between the suffrage movement in the States, and the native communities that lived in the early, you know, the 13 colonies area.

And we're absolutely thrilled when Mary Mackey, who has been a guest on our podcast a couple of times, said that she knew you and that she would connect us to you.So welcome.And thank you so much for being here.

I'm so delighted to be here.Looking forward to the chat.Thanks.

Would you like to introduce yourself to our readers and talk a little bit about how you sort of got interested in this topic and and drawn into the research of it?

Well, I think it begins when I fell in love with the dead suffragist Matilda Jocelyn Gage, a woman who had been written out of history, who actually her granddaughter was a friend of my mother's.

And just in this sort of unusual, fortuitous way, found out that this woman who I had known since childhood was also the granddaughter, the namesake, and the only living grandchild. of famous suffragists, and she had her grandmother's collection.

And it was, well, I'm going to just stray to that for a minute, because it laid the framework.She, I asked for, I actually, I have to confess, I hated history.I, you know, it was great men, great wars, great dates, and had nothing to do with my life.

And as a radical feminist in the streets, I had nothing to do with the suffrage movement.You know, these teacup ladies who asked for the right to vote for 72 years.

That was the story of the suffrage movement in the 1970s, the early suffrage, the early 70s.And so, but I thought, you know, I had,

been part of the creation of one of the first women's studies programs in the country, California State University, Sacramento.1971, I taught my class.I'm still teaching today. 15 minutes later, anyway.

You know, just a little piece of information there.Anyway, so the suffrage movement was something I knew I needed to cover in my class on the introduction to the women's movement. But boy, I didn't want to talk about it.

So I would bring somebody in who had an interest, and they would talk about it.And I would leave.But I thought, wait a minute.

I might be able to get a really good anecdote, one good story from my mother's friend, Matilda Jewel Gage, about her grandmother.So I, when I was back in South Dakota in the summer of 1973,

got into my van at the lake almost didn't go and drove into Aberdeen an hour in 100 degree heat with no air conditioning.You're that close to this not happening.And if I hadn't gotten in that van, we would not be talking today.

So that's the origin story.She had all of her grandmother's correspondence with the family.She had piles of Published and unpublished manuscripts.Oh, wow.Family scrapbook.She had brought it all out for me.

One of the first letters that I picked up and read was to this effect.I'm not going to give you the exact words, but Mrs. Stanton is the Benedict Arnold of the movement, but she is nothing compared to Susan B, who has destroyed our movement.Wow.

Now, my immediate reaction was, this is a malcontent.You know, this is somebody who, she's a minor actor.I, you know, I've been involved in the movement.People see things differently.

But then I started going through and I realized that she was part of the leadership triumvirate. of the National Woman Suffrage Association with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

And, you know, grew up on Nancy Drew books, mysteries, and you're going to have to solve this dilemma.What is the meaning of this?What is the letter to Sally?Who was she writing?The letter was from Matilda Jocelyn Gage to her son.Ah, okay.

She is, there's something going on.Well, I, you know, later found out after 50 some years of studying exactly what was going on.

And I tend to agree with her that Susan B. Anthony destroyed the movement because the women were fighting for reproductive rights, for equal pay, for legislative changes, for an end to violence against women,

And Anthony took the movement, moved it into a single push for the vote.So anyway, that led me to Matilda Jocelyn Gage and her major work, Woman, Church, and State.It's online.It's searchable.

It is, I think, not only a feminist classic, as it's been called, But in some ways, what she does in this book is to define the relations of reproduction and the reproduction of daily life in the way that Marx defined the relations of production.

It's an absolutely brilliant analysis.But I was, the hard pressed question for me was, Here is a woman who is not looking for equality, okay?She's looking for an end to patriarchy.

At the end of Woman, Church, and State, she says, you know, we're in the middle of a revolution.It will, every existing institution will be destroyed.The result will be a regenerated world.Now, how does she get

If you're in a system of oppression that is so complete that you can only see, well, what would it feel like to be equal within this system?How did she jump out of that system and see beyond it? This is how we can transcend the system.

This is how we can replace patriarchy.She had to have seen something that gave her the sense that that was even possible.This is what it would look like.

And I remembered when I read about the Arapash, trying to think who was the anthropologist, the woman who said, It is as though the men have a concept of women that makes rape unthinkable.

And when I read that, it was like all of a sudden rape changed from being a part of natural behavior on the part of men to being institutionally created behavior.And I thought, I saw that.What did she see?

Well, this is where I have to own my racism, because I read Woman, Church, and State numerous times.It came out in different forms.I wrote introductions to it.I edited it.I did all kinds of stuff with it.And I never saw that

In the first chapter, the first few pages, Matilda Jocelyn Gage says, never was justice more perfect.Never was civilization higher.Why didn't I see that?Because when I finally got honest with myself, it was because I had

Beneath my knowledge, you know, Leonard Cohen says, sank beneath my wisdom like a stone.And I feel like my racism sits below my wisdom like a stone.And that racism said, women are beasts of burden.Indian women, no, 10 paces behind the man.

What would they have to show or teach white women anyway?I didn't even know it was there, but it was, and it kept me from seeing it.

I got a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship to study the story and to look for how did she get that transcendent vision.And that was when I took a deep breath and got into my own rhythm and saw that.

And it was, that was the transcendent moment.That was the moment of, there's something here.And it was, who were the Haudenosaunee anyway?What, are they still around?What's this about?I mean, that is the level that I started from.

I mean, you want a lower level of dumbness?You'd be hard pressed to find one. The, what I started doing was just reading what Matilda Jocelyn Gage read.What did she cite?And then I thought, well, what did she read in the newspaper?

So I went through actually 300 years of, you know, contact eventually, because there were some questions that I just could not get my mind around the answer that was there.And it was like, no. This couldn't be true.No violence against women.

Violence against women treated so seriously.Could that really be true of an entire culture?And it was like, look through 300 years of contact and see what you find.So it set me off on a pursuit.And it was at the time,

I remember thinking if a graduate student had come to me and said, I want to study this, I think that there's a connection.I would have said, I, you know, I think that's probably a wild goose chase.

Wild goose chase.If there, if there was evidence of it.

we would know that it would be out there people would have so it was this sort of um feeling a little bit crazy through this because it was like am i really seeing this is this real and if it is why hasn't anybody seen it yet why isn't this talked about yeah so

That was the origin story, a long story.

I think that happens a lot.

We find, Dawn and I, in this stuff that we've discussed on this podcast, that the idea of feeling crazy because there's all this information that's out there, that's at variance, that counters so much of the, you know, for want of a better term, patriarchal narrative of how the world works.

And then it's just kind of either overlooked or dismissed or hidden or buried.And then you go, I can't be seeing this.Am I seeing this?So I think that's a very.Yeah.

Yeah.And then why isn't everybody else seeing this?Like it's right there.It's right there.Yeah.

Yeah.Oh, yeah.That's reassuring.Yeah, absolutely.A common pattern.Yeah.As we're as we're. Really finding the deeper truths, finding the true history.History isn't what happened, it's who tells the story.Absolutely.

And so we're starting to tell the story.The outliers are telling the story.

I sometimes think it's also who makes the movies about it, because that's everybody's view on how it actually looked, even though it's no relation. I think maybe a good thing now is we have so much information that we can access.

So, you know, obviously when you started the journey, it took go through 300 years.I imagine you had to go into microfilm and old documents and all kinds of things like that.Uh, so, I mean, it's amazing undertaking on your part.

Well, it was, you know, to begin this process before the internet.

The process has changed so completely.There are obscure manuscripts and publications that I would have to wait a year for, you know, through the interlibrary loan circuit.And now they are online and searchable.

And so it's like, I have to go back and replicate research in a more, you know, sort of, oh, I can look up this word, and I can find every reference to it.I don't have to go through 3000 pages.

Yeah, yeah, it's wonderful.Yeah, much more user friendly.Yes.The thing that that I think really struck me as I was reading your book was

It was such an unexpected notion how much cross-pollination and just how much contact there was between the people living on the East Coast, the Euro-Americans,

and the Native Americans because we live in a world now, I think less so since the whole pipeline crisis and that hit the news, but it feels very much like we live in a world now where the majority of Americans don't have daily contact.

with Native Americans, with the indigenous population of this country, and that that seems like a very far away foreign world about which we know nothing.And from the letters and the newspapers and the

you know, the daily tear sheets and all that sort of thing that you were mentioning that had article after article about Native culture, about interaction with Native life.

It shocked me how much our ancestors would have known about this culture that we don't know anymore.We have lost that.

That was a really important part you've hit on, of the discovery, if you will, that who knew?But when you think about it, okay, the process of the settler colonialists moving into, you know, West,

they're coming into a place where there is a highly evolved civilization.They immediately attempt to destroy it, but they also are learning from it at the same time.And so it's the Thanksgiving story over and over and over again.

You know, the people in Syracuse, I remember, you know, riding around with one of the clan mothers from Onondaga.And she said, let's go find that

that was a sign, you know, and she said, that's the one that talks about how the people of Syracuse would not have survived without us.You know?It's, there was so much learning.You're coming into a land that you don't know what it is.

You don't know what's going on there.And unless you listen to the people who live there, You won't survive.

And, you know, the value system of the Haudenosaunee, which is, I think, pretty typical of indigenous cultures, is that you take care of everybody.And so it wasn't like, well, these are white people, we shun them.

It's like, they have needs, we'll take care of those needs.And so the contact, you know, sort of daily contact before the reservation system was set up.I think it was, you know, this is in a process of change.

This is in a process of learning and destroying, learning and destroying.

Yeah, yeah.But such a close contact, even though it was of a destructive nature, meant that the ordinary person, the ordinary Euro-American settler would have

been aware of the Native culture and the Native practices and would have probably had opinions on it and would have written of those opinions in lots of original source material that we can find and hopefully, you know, learn something from.

Yeah.And if you think about just that proximity and that contact, here are white women who are encased in 20 pounds of clothing hanging from a waist that is being squeezed, squeezed, squeezed with corseting.They're in heels that are upending them.

They're held captive by their clothing.And they're looking at women who are wearing you know, loose-fitting tunics and moccasins and have a vitality that they can't even imagine.

These are women who they know are not suffering in childbirth the way that they are.So why?What's going on?You know, you just, they would see the difference.I mean, when I'm hanging out with Haudenosaunee women, I am just, and this is 2024,

with all the attempted colonization that has attempted to destroy the culture completely.I'm around these women and I am strengthened.And it's just their presence, their sense of personal integrity, the way in which the men are treating them.

You know, I'm changed in the process.This is 2024.Imagine if I was a woman who had no legal existence, you know, which under the Blackstone Code of common law, women were considered dead in law.

My husband on his deathbed could will away a child that I'm carrying.And that child would be taken away from me. And I would have no legal recourse.I had no right to my body.I had no right to my possessions.I had no right to my ideas.

I had no right to live where I wanted to.I had nothing.And I'm looking at women who have all of that and more.And moments that have just absolutely transformed them. Yeah, it became possible.

Yes, yes.And and, you know, it's true of any oppressed people.I would I would venture that.Oppression never becomes.How do I say this? When you have your rights taken away, you know your rights have been taken away, right?

Even if you look at a system where you are on the bottom rung of the ladder, we are all human beings and we all have needs and desires and wants and loves and passions and all that sort of thing.

And you look at a system when you're on the bottom and you know it's unfair. You know it's unfair, even though you may not be able to do anything about it.

So yes, what you're saying, what a revelation it must have been to be trapped in the system that you would know was working against you.And to see another culture right there in front of you where that was not the case, I mean,

must have blown their minds.

There is this moment when you see that, but when the hegemony is so complete that this is natural, this is biological, this is just the way it is, that's when I think you have to have an alternative that says to you, it can be different.

All you see is, this is exactly the way it is for all women.I mean, I think we still experience that today.You know, that the mystification, you know, the women who are wearing heels that are destroying their bodies.

And they're saying, I do this, not because I'm forced to culturally, I do this because I like the way I look.You know, it's that sense that I have individual agency, rather than I'm being constructed socially in my options.

And that mystification has to be broken through in some way, before I think we can see this is oppression.

Yeah, Sean, you were gonna say, I was, you know, to your point of a person's own awareness of their own humanity.

I think what happens in these systems like this, whether we're dealing with gender or whether we're dealing with ethnicity, it's the idea of the system may tell you and try to emphasize to you that you are less than or dehumanized, there's some lacking or something different, but you yourself know who you are.

You know your own consciousness.So like you were saying, you're aware that there's something amiss.

And then like Sally's saying, if you can see another way that helps you break through that, certainly that's where something special happens when you can have that contact.

I mean, I found, like you say, Sally, that if you're on a reservation, let's say, there is a sense of groundedness in the culture for men and women that is really refreshing and really sort of enlightening.So, yeah.

I can imagine what it would have been in 1840 or 1860, you know, to have that experience.

So Sally, tell us a little bit more about as you were doing research and finding these documents, what kinds of thing did you find?So in what, give us some examples maybe of some of these,

moments where the women of the suffrage movement in the United States were drawing on values that they learned from the Native populations.

Yeah, I think one, let me give you one example.Matilda Jocelyn Gage was editing the official newspaper of the National Woman Suffrage Association.

And there was a bill, this would have been in 1878, there was a bill introduced into the New York legislature that would have given suffrage to Indian men, would have given the vote to Indian men.And What would a suffragist write about this?

Would she even know about it?Would she even write about it?

Well, she writes an editorial in her newspaper where she says, the chiefs have met at Onondaga, as they have since before Columbus, and they have decided that they will not accept citizenship in New York State or the United States.

And then she goes on to say, they are citizens of their own nations.They are sovereign citizens of their sovereign nations.And to force citizenship on them would be like forcing it on Canadians or Mexicans.They are sovereign nations.And she says,

Is it the greatest hypocrisy that the women citizens of this country are demanding the vote and being denied it, while Indian men who don't want it are having it forced on them, the better to steal their lands?

Justice to the Indians requires living up to the treaties that we have with them."And then she goes on to say, You know, maybe we could learn something from them.

The chiefs that visited the White House last New Year's and brought their cards, their calling cards, and on the back of each one of them was a broken treaty, was an example of a treaty that was broken.So, I mean, look at this tour de force.

First of all, I remember the first time I read this was in special collections at Syracuse University.And I was with an Onondaga Nation friend of mine.

And I remember Jeannie read it and she looked over at me and she said, I can't believe a white woman understands sovereignty to that degree.And especially then, And Jeannie became the vice president of the Matilda Jocelyn Gage Foundation.

You know, the connection, it was like, yeah, this is an ally from the past.

But the fact that she defines sovereignty in those absolute clear terms, that she recognizes, she has contact with the Grand Council and knows what the Grand Council is deciding. of the Haudenosaunee.

This is when all the chiefs come together and, you know, to decide by consensus.And she knows the process.She recognizes what their decision was.She respects that decision.

She shows the hypocrisy and the, you know, the con, you know, here's what you do to white women.Here's what you do to Indians.You're screwing both of us. And then to take direction, knowing what their strategy is, and taking direction.

I think that single editorial is just, it changes the whole narrative.

So from an outside perspective, if you look at a council of the men,

if you're a Euro-American looking at the way that Native American culture was sort of assembled, and here is a male chief talking, you would assume, OK, well, that means the men are in charge.But that's actually not the case.

Can you explain a little bit about how it actually works?

Yeah.I'll tell you a personal story. The first time that I actually met Tadedaho, Tadedaho is the chief of chiefs in English, and that doesn't capture it at all.When I met him, he said the strongest thing anybody has ever said to me.

I thought the top of my head was just going to blow off. It was a joke, it was a test, it was, I mean, it was so much condensed.What he said to me was, no woman put me in my place.

Now, if I was a Western feminist hearing that through Western feminist ears, I would have been offended, right?He was humbling himself in front of me.

He was saying to me, every other chief is put in place by a woman, and he is responsible to that woman.If he misbehaves, that woman will give him a warning.And if he doesn't listen to her, she gives him a second one.

And if he still follows on his path and not the needs of the people because she's the ears and eyes of the people and he's the voice, but the voice has to listen to the eyes and ears because that's who he's representing.

If he doesn't listen the third time, she cuts off his heart.As Elizabeth Cady Stanton described it, she removes him from office.

What he, you know, if I'm thinking about the model of my Western world, I'm seeing chief up here, dot, dot, dot, everybody below, turn it on its head.Here's the woman up here.Here's the man down here.Okay.

Now you have Tadodaho, who's chosen by the 50 chiefs. He is not responsible to a single woman.He's responsible to 50 women.If you think about it, there are 50 women above him telling him who he is and what he must do.So I got it.

It was that pivotal moment.If I would have responded, as a Western feminist in my power dynamic of power over, I would have been offended.Instead, it was like, I couldn't even look at him.I could not even look at him.

I really literally thought my head was gonna explode because it was, it was the most powerful thing anybody has ever said to me.And all I could do was look down and say, I know.

Well, in a way it's the ideal that America has and what our leadership is supposed to be, that we are a servant of the people.It's supposed to be structured.

And of course we know the influence that native culture had on some of the structures that we created in America.So I think that's a wonderful example of it. of just really having a responsive to people, serving people.

Not just even obviously the gender dynamic, but even just the citizenship, the human, the societal dynamic.

You know, I had lots of, when Trump was president, I had some really painful discussions with grandmothers, with friends.And they said, why do you women allow him to stay in office? we would remove him in a minute.

He would never, ever be in a leadership position.And it was sort of like, what's wrong with you?What's wrong with your system?How can a man like that, who would never exist in our culture?And this is after how many years of colonization still?

Yeah, I was struck by what you wrote about the things that a male chief was evaluated on, and that one of the most important things was that he was a good father. that he showed that he was responsible to his own family.

Because if he wasn't responsible to his own family, how could he be responsible to the entire clan, and so on and so on?Yeah, exactly.

Right.Yeah.You know, and the way in which traditionally and still living in proximity, even if it's not in the same longhouse, The grandmothers are, you know, they're watching these boys as they grow up.

And the clan mothers are, you know, they're watching their grandsons and they're not watching for the boy who puts himself first.They're watching for the boy who's sitting back, looking at who needs what and responding to that.

And then they begin grooming them to be the chief.You know, they can do this from an early age and they watch the qualities. when they play lacrosse?How do they play?The women are watching the men as they're playing lacrosse.

And if somebody does something individually for themselves, rather than what's the best for the whole team, women are like, he's not one.

And so, you know, watching that dynamic where the women are so respected, it's, you know, part of the friendship dynamic that I have is that it's like, oh, I'll just be hanging out with friends. something will happen.And I'll go, Oh, my God.

Do you realize what just and for them, nothing happened.

And for me, it was like, I have never seen a male do that.Or I have never experienced this dynamic.And it's like, What's wrong with you, white girl?I mean, it isn't exactly that, but it's like, you know, this is normal.

This is the way life is, and it's not for me.And I have, you know, I mean, I have two grandsons.I have a son.I have wonderful men in my life.

They're culturally creative men.

It would be great if, not just even politically, just what you're describing,

In an economic system that we live in where the idea would be that you lead by helping and by sharing and by because I think that is also right now, particularly destructive in culture.So it's a great model role for people to look at.

Yeah, what Genevieve Vaughn talks about with the gift economy, that it's universal giving to need, and that you distribute the necessities of life amongst the community so that everyone is cared for, that everyone is taken care of.

You know, a Lakota friend of mine one time said, you know, we know, we call white people washichu.You know what that means?And I said, well, what does it mean that these are men who have hair, people who smell, they got white skin?What does it mean?

He said, he who takes the fat, it means that human beings would never take the best for themselves.They would give it away.So these are creatures who don't, who don't do that.So what are they?They're those who take the fat.

Yeah, yeah. who aren't thinking of the community first.And, you know, seven generations, that mentality of, you know, caring, making decisions that will, that will have positive effect all the way into the future.Yeah.Yeah.

You told me.And those decisions can take a long time.You know, when you're working with consensus and you listen differently, You know, instead of, okay, what's wrong with this idea?I'm gonna knock it down.That's how we learn to think.

We learn to think in debate, in win, in over.And instead, it's like, okay, what part of what this person is saying can I relate to?And if there is not consensus, you go back and you think about it, and then you come back.

And sometimes it can take tens of years before you come to consensus, but you can't move forward.You know, the sort of, the system that we have is so dysfunctional because it's like you get winners and then the losers are pissed.

And so they're going to become the winners.And so, you know, How do you make progress?

How did when Tilda Gage understood this and developed this, how was it received by other suffragists at that time?As you say, she's sort of written out of history.Was it initially something that was embraced?

Was it actually something that was just not understood?How was it taken in and thenYeah.

That's such a good question.And the answer to that is so complicated that I'm still working on it.Because, I mean, it's an essential question.And it has to do with what's happening with the movement.I think that there were.

Okay, I'll just give you my quick and dirty.Okay, sure.Yeah. this is the best I can give you at this moment.

I think that the degree to which they, an individual woman, an individual suffragist, was able to disengage herself from Christian exceptionalism.

The idea that this is the only way, and these are savages, and if we love them, we have to force them into becoming Christians, okay?The degree to which they can, and I think Stanton and Gage were the two who were most able to.

There's another woman, Helen Gardner, who needs to be studied more.There's some other women, but it's almost like individual woman by individual woman.You know, how much was Clara Colby able to?How much was

And that's the degree to which then they can embrace this information.Both Stanton and Gage are writing about this in the late 80s.And this is a moment when Stanton and Gage say,

Look, we've been fighting this fight for how long and how far we gotten.And it's because of Christianity.It's because every single thing from dress reform.

No, you're going to go to hell because woman shall not take it unto herself that which pertaineth to man.So they start wearing pants and they're going to hell.The idea that that God defined woman as subordinate to man.

And so if woman tries to stand next to man at the ballot box, she is destroying God's divine plan.You know, every single step of the way, the church is the end.And, you know, gauge struggles with do I call it, you know, ecclesiasticism?

Do I call it Christianity? She just says, it's the church, boom.So they say, that's what we have to go after.

And that's when they're writing on the Haudenosaunee and indigenous women in some ways generally, both Stanton and Gage move even beyond the Haudenosaunee and make this connection with indigenous women.That's when that starts coming out.

Now, boom, this is also, Two years later, 1890, Susan B. Anthony creates a merger between the conservative women's movement, the American Women's Suffrage Association, and the National.And it's really a takeover of the more conservative.

And the idea is the vote only.So what happens strategically is that, oh, the vote, we've got to win the South.How are we going to win the South?Anthony deliberately, and in Ida B. Wells' autobiography, it's spelled out right there.

Anthony says, I have to practice expediency.Personally, Here's how I fight racism.And she supports Wells, and Wells tells the stories of how she supports her personally.

But when she tries to explain to Wells that she has to practice white supremacy in order to win the South, no, Wells will have none of it.But racism then becomes the policy of the National American.

They make the argument, give women the vote, because white women outnumber Negroes and immigrants, and women's suffrage is a way to maintain, and they use this word, white supremacy and native-born supremacy.

That is the policy of the National American. Now, what do you think they're going to do in terms of Native American influence?And I think it's part of the reason they write Gage out of history.

It's also the strategy.That's the best I can give you, Sean.It's incomplete, but it's almost like it's got to be woman by woman, by year by year.

No, it's it's what's amazing to me about that.And it's you know, we're not necessarily surprised by it, but that's the exact same strategy.That's Nixon's southern strategy.That's the Democrats central center strategy of the 90s.It's the same.

It's just repeats itself in different form. like a horrible monster who keeps coming back.

And it feels to me like, like, yeah, that it's almost a it's like patriarchy perverting the idea of consensus and replacing it with coalition. which is, I want this one thing.

So in order to form a coalition with you, I'm going to give up these values so that I can form a coalition with people that I fundamentally disagree with.But I want to get this one thing.So I'm willing to do it.

And how that replaces the idea of consensus, where You just keep talking until you find that common ground and you hopefully can convince people that what you feel is best for everyone is indeed best for everyone.

So it's kind of an interesting, like Sean always talks about patriarchal Aikido, like the patriarchy takes this positive energy, flips it and uses it to serve the patriarchy.

And it feels like that coalition building is like consensus flipped by the patriarchy and turned into something that can serve the patriarchy instead of dismantle it.

Boy, that is such a good analysis.You know, one of the things that I did a woman's suffrage movement anthology for Penguin Classics.And one of the things that I really struggled with that was the idea of the inevitability of history.

You know, that these are the parameters, so this necessarily is going to happen.And what I tried to do is to disrupt that a little bit, thinking about what if they had made different

community, you know, alliances, what if they had instead, what if the suffragists would have made an alliance with the immigrant men who could vote?

What if they had made an alliance with the African American men who could vote and strengthen their votes?And instead of working for Jim Crow laws, which they did, if they would have had a different alliance, and

And the other thing that I really started thinking about was what happens when you throw somebody when you make that sort of partnership that you're talking about, you throw somebody under the bus.

Okay, so you throw African American women under the bus, which they did, you know, African American women really not for a hundred years until the Voting Rights Act in the 60s.

But, and even now, and the loss, to think about, I mean, you look at the leadership of African women, African American women today, and you think, what if we had had that leadership for a hundred years?You know, the incredible loss.

So when you throw somebody under the bus, you may win the battle, but you lose the frigging war.

It's interesting when you say the inevitability, I think it's part of the part of the dynamic we get in a patriarchal culture is the sense that this construct is so powerful that the I've noticed this.

I've seen this in the last few decades, just in different social movements or developments, and you have to play to power.That's always the idea.

You play to the most powerful to get what you want, and it becomes the kind of thing Adong was talking about, where you just decide, okay, I'm going to go along with this.I'm going to reinforce this structure.

I'm going to get my thing, but nothing changes.The structure remains as it is.

You get some crumbs and you get to be, it's, I think it's the way I've said it to people is, you know, you can choose, you can choose to have us want to seat at the table, or you can choose to build your own table and sit where you darn well please.

And it's usually people want the seat and the head of the table never changes, but you get to sit next to the head of the table.And that's kind of the way it sort of plays out. Yeah, yeah.

So, one of the ways, I hope, that we can disrupt this is by writing books such as you write and letting people know, you know, just as these, just as Matilda Gage and to some extent Elizabeth Stanton

did in their time was to write about these alternatives and spread the knowledge of these alternatives because we do, when we are locked into a system where we don't see alternatives, then we don't know how to rage against the machine, as it were.

But if we spread the word about these alternative systems that are much healthier for women and humans in general, then I think that is

that is a way to hopefully start to eat at the foundations of patriarchy and other disruptive and dangerous structures that govern our lives right now.

You know, there's one thing that I would add from my experience that absolutely, I think that's all.But when I started doing this reading, and I just read

the primary sources and every chance I could get to find the native voice, you know, finding that.I didn't even read the experts on the Haudenosaunee, right?So I finally come back to them and it's like, what are you writing about?

This isn't the people that I know at all, you know? And I realized two things.One was that I was most likely to get it wrong as a white scholar and that I was most likely to do damage.

And so I really took a step back and I decided that I would not publish a word until the Haudenosaunee asked for it.If they never asked for it, it would never get published because it had to be on their terms.Otherwise, you know,

I didn't trust myself and I still don't.So I, there was all sorts of things that happened.And a haredeshoni man, when I gave a paper, asked if he could

get other folks in touch with me and Akwesasne notes asked for the very first thing that I ever published was the paper that I gave at that conference.And then I didn't publish again until Northeast American Quarterly requested something.

And then when I did Sisters in Spirit, that's not a major publisher that did that.I found a publisher that would agree And they publish Haudenosaunee materials and have connections.

There were personal connections that Haudenosaunee friends of mine had with book publishing.There's a whole long history there.And they agreed that if at any point the women at Onondaga wanted that book pulled, they would pull it.And so it,

I'm very, very cautious about and trying to find, you know, how do I tell the story that I know without telling their story?What are the boundaries?And I don't do it well.I do it by the seat of my pants.

I do it the best I can any moment, but it's absolutely imperfect. And it's, yeah.Trying to be a responsible ally.It's not, yeah.I don't do it well.I mean, I'd like to say it's really hard, but.

I think it's more honest to say, I just don't do it well.I do it the best I can.

Yeah.Yeah.How to tell these stories without telling someone else's story in place of them, rather than tell the stories that are yours and encourage the listening to the stories that other people tell.Yeah.

That I'm the opening act.If you want to get the real story, you listen to it and you show anyone.

Right, right.You go to the source.Yeah.And allow people to tell their own stories.Yeah.Yeah.Wonderful.Sean, do you have any final thoughts or questions or?

No, I think this is, I mean, so many of the concepts, you know, things that we talked about and brought up, but also I'm glad that we were able to have this discussion, Sally, just to bring this culture and the cultural contribution to light.

And thank you for the work you've done on it.

Well, thank you for it.I really enjoyed it.I've got new thoughts and new questions.Sean, I'll be working with that one about, you know, what at each point, you know, who heard, who didn't hear that?Yeah.And the whole patriarchal placing this in

the context of, which you both do so well, to place this in the context of, you know, where are we in terms of the struggle against patriarchy?And how do we understand our behavior in this moment?

That's really, you present and create some really good handles for that.Oh, thank you.And I'm grateful to you for that.Thank you.

Thank you so much.Thank you so much.And thank you again for joining us today.This has been a wonderful discussion.And thank you, Sean.

This is the 34th Circus Salon.Make matriarchy great again.

Take care, everyone.And blessed be.Thanks.

Sign in

Sign in Sign in

Sign in Sign in

Sign in