The idea of magic isn't only reserved for life's grand moments, it can live quietly within the ordinary.Most everyday objects, a glass of water, a plastic lamp, hold unexpected complexities and beauty.

When we look closer, these items can transform into portals, revealing surprising realities.And to understand this magic, we've continually turned to art and to science.

Have you ever seen patterns in floor tiles and felt like you might be glimpsing into hidden worlds?Or touched a metal fork and thought about the particles moving inside of it, keeping it solid?

How do artists and scientists tap into this childlike wonder to reveal the extraordinary in the everyday?Join us as we explore these questions and discover the magic in the mundane, here on Edge of Reason.

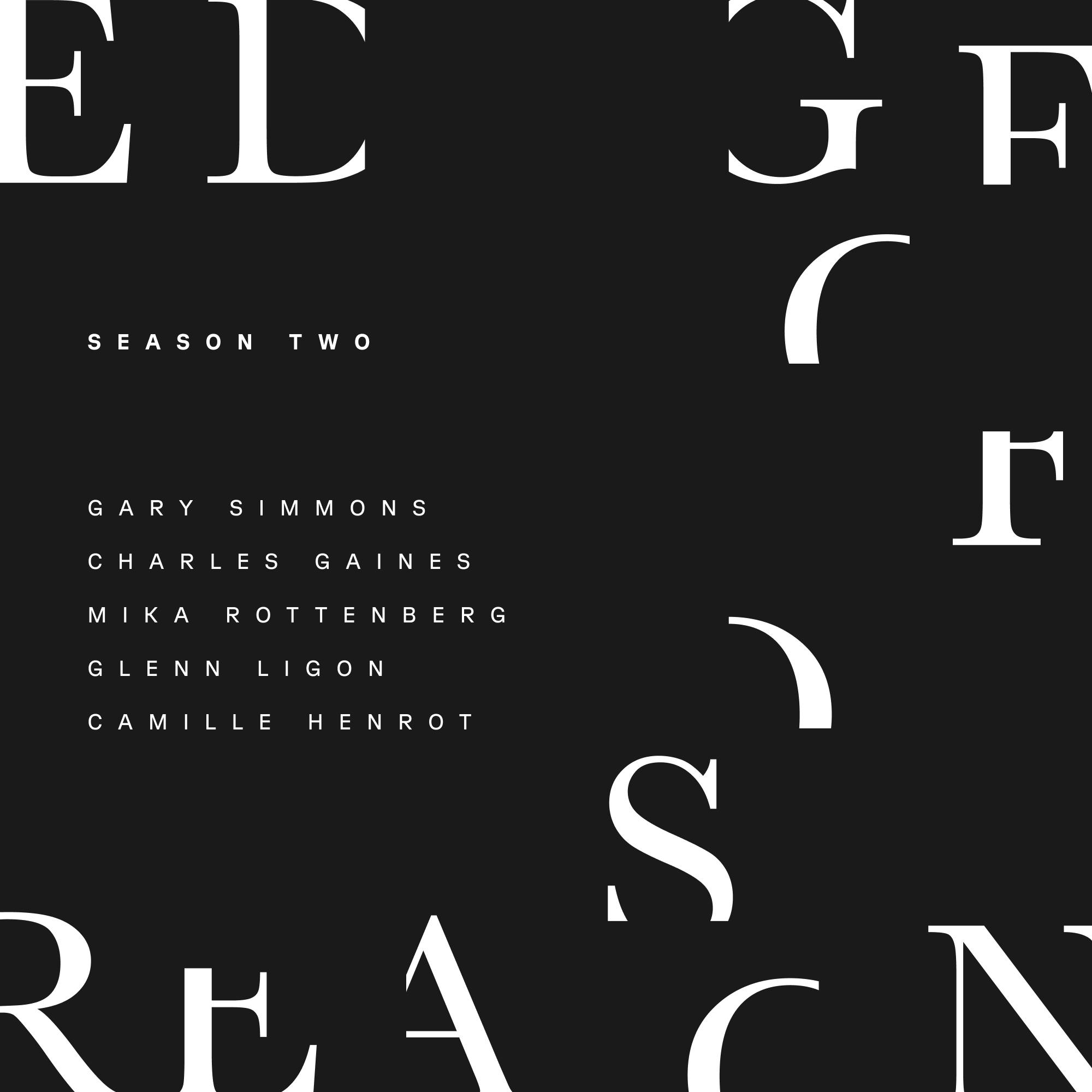

podcast produced by Atlantic Rethink, the Atlantic's creative marketing studio, in partnership with Hauser & Wirth, a home to visionary modern and contemporary artists.

This season, we explore the line where the left brain meets the right brain, where logic and reason end and creativity begins, and how personal and universally resonant themes connect art with the human experience.

Today, we're joined by two creative visionaries who help us find wonder in the world around us.

Mika Rottenberg, an artist known for her work in video sculpture and installation, transforms the everyday into something remarkable, using familiar objects and settings to explore themes of labor, value, and our connections with the environment, the global economy, and one another.

We also welcome Dr. Felix Flicker, a theoretical physicist who specializes in condensed matter.

and studies how the ordinary materials around us, like metals and crystals, hide extraordinary properties that allow us to look at the world with fresh eyes.Mika, we're thrilled to have you here on Edge of Reason.

I wanted to start off by giving listeners an idea of the narrative and emotional breadth of some of your work.You've created videos.Videos featuring elaborate, seemingly purposeless machines maintained by unseen labor.

A video of a Chinese restaurant that serves up miniature businessmen that's also tied to the underground economies of the U.S.and Mexico border.And a feature-length film in which portals connect women around the world in the near future.

You've spoken about your fascination with how we are made of materials and how those materials consume us as we consume them.Can you recall when this fascination began, maybe even a moment from childhood?

You know, I have this one moment looking at my grandma's bathroom tiles that would actually lie on the tiles and just, you know, like you find in the clouds, like shapes and stuff.I just have a memory of finding like whole little worlds in it.

And I love to make little holes too.I'd like, I would play like dentist or something and like dig little holes. So, you know, that's kind of one moment.

I think I was always interested in mechanization, but I wasn't the kid that was like fixing anything.I was more like breaking it down or gluing it to stuff.

But, uh, yeah, just, just the way things work, the way things are, but from a total like poetic astonishment, uh, never from a kind of a scientific or, or that kind of aspect.

Well, your work uncovers ideas about production and value and the circulation of materials and objects, which are ideas that seem to me to be closer to economics than to physics.

So I'm curious to know, what drew you to visit CERN, which is the European Organization for Nuclear Research in Switzerland, and also a kind of a mecca for particle physicists.

I was researching for a new piece and I wanted it to be about matter.It's a big topic, right?But kind of thinking about materialism, both the philosophical theory and also, you know, capitalist, like new materialisms.

There was a book that I was reading and I was really into. My work has always been about all these hidden forces in objects and things that we interact.

I think I say that we consume and in return consume us back, but I don't know who consumes who first.And then I was also really fascinated by machines, as I said. And scale.

So I was really into this is like the biggest machine ever made to find the smallest particle that ever observed.Then this whole piece spaghetti blockchain is about scale in a way.So it kind of made sense to go there.

And then apparently they do have an artist residency.So I ended up doing that, which was great.

So you have a show that was inspired by your time at CERN and the work that you got to witness around the Large Hadron Collider that you called Antimatter Factory.

And I'm wondering if you could share how pieces in the show like Spaghetti Blockchain were influenced by your experience there.

You know, I think I look at things from a visual surface value and surface doesn't necessarily mean flat, but it could.Like I kind of knew how the machine looks like and I knew that the Higgs boson, that thing, there is no shape to it.

Like I won't be able to see that.

For our non-scientific listeners, the Higgs boson, often called the God particle, is theorized to be the fundamental particle responsible for giving mass to all other matter in the universe, and its discovery at CERN in 2012 is considered one of the most important achievements in modern scientific research.

I was blown away that they put tinfoil on everything because I think this is more for like math labs or in artist studios and stuff.So I was amazed that they actually put tinfoil from the supermarket on these machines.That was a revelation.

Okay, well now let's bring in Dr. Felix Flickr, a senior lecturer in physics at Bristol University and the author of The Magic of Physics, Uncovering the Fantastical Phenomena in Everyday Life.

Through his work, Dr. Flicker helps us deepen our appreciation for the beauty embedded in the familiar.Welcome to Edge of Reason, Felix.Thank you for having me.Felix, I wanted to start with the same question that I asked Mika.

Was there a moment, maybe in childhood, when it was clear, oh, Felix is going to be a scientist?

There was no particular moment.I basically always wanted to be a scientist since I can remember.I definitely, by the time I was four, which is about as early as I can remember, I liked the equations, the weird symbols for things.

You know, they're sort of like, I don't know, like magic spells.When you're four, you don't know what they mean, but you kind of know that they have some power to change the world and they look kind of cool basically.

So now you work in condensed matter physics.What is that and how does it help us to see the magic in the mundane?

So it's the study of the stuff around you, basically, matter, like solids, liquids, and gases.But it's also this working out of how the stuff around us comes about through the really quite strange world of quantum mechanics for individual particles.

We have these elementary particles like electrons and protons and things, and those things behave really weirdly, but somehow they add up in a lump of matter to give you mundane stuff that you wouldn't really value typically.

But it's got that kind of magic hidden within it.

With astrophysics, say, when you're looking at black holes, or you might be doing cosmology and looking at the whole universe, there's something inherently quite exciting or magical about thinking about the biggest possible things.

They're very different to your everyday world.Then there's also something similarly magical about thinking about the smallest possible things, like the individual particles.They're something very different to our everyday world.

The matter that's around us, you sort of think, well, that's a bit mundane.That's a bit boring, because I'm familiar with that.My entire experience is like lumps of stuff, so it's sort of not got that magical appeal.

So I wanted to try and explain why studying lumps of stuff around us is actually, I think, as magical as looking at the extremely small and the extremely big.But that's what it is, essentially.

The world around us, the familiar world, but how it comes about from this unfamiliar world that's kind of hidden beneath.

How would you summarize what you do as a theoretical physicist working in condensed matter for somebody like me who flunks physics?

Well, as a theoretical physicist, it sounds very fancy, but all it means is we don't actually do any experiments.A condensed matter physicist would specialize in matter on various different scales, and experimentalists would come to us with results.

We try and work out what's going on by thinking about what the particles are up to, basically. There's a kind of catchphrase for it, I suppose, which is that the whole is more than the sum of the parts.I think that's the simple take home message.

So it's like, it's made up of these individual particles that are individually weird, but when they come together, they make something fundamentally different to those particles.

So it might be like, you know, you can take a load of water molecules and you can stick them together and they make water, but they could also make ice.And that's very different to water.

So there's something more than just the individual molecules there.And that difference is the thing that we'd like to study.

Hmm, okay.Well, we have the artists and the theoretical physicists, and it's time to bring you all together in conversation.So to get started, I wanted to ask, what role does curiosity play in each of your work?

Mika, I know you're drawn to finding hidden worlds in everyday objects, and Felix, I know you've written about the magic in things like crystals and clouds.Where does curiosity begin for each of you?And how do you choose

the materials that you want to explore and work with.

I'm not sure if it's curiosity because it's, I seem to be very curious or gravitate to certain things and certain things I'm not, you know.I feel like my brain is very single track and there's like something that is in there.

And I think it's movement maybe that I'm really fascinated by.And, you know, I love that.I think it's physics in general.There's so much movement, right?It's all about kind of movement between these particles.

I think it's more gravitating to a certain thing, and that might be forces and movements and something like that, and then getting really curious about that.

I agree.There's a sense in which you feel like you're supposed to be generally curious about the world, but in reality, it's more like there are specific things that I get obsessed with, and then neglect everything else.

And then it's a very strong obsession, but I've never worked out exactly what it is that is the underlying thing that links them.

Felix, I love what you said about the specific obsessions that drive us, that pull us towards certain forces and ideas.

And Mika, your work seems to reflect the same kind of sense of focused fascination, especially in your time at CERN, where you were surrounded by the world's largest machine studying the tiniest particles.

How did being at CERN in that environment, observing physicists working with antimatter, how did that influence your practice and your thinking about your art?

I wasn't so much observing them because I think it's the machines spit out data, right?And then they look at it.So I was looking at the machines, which most of them are magnets, right?Like all the massive is basically the magnets.

You know, I'm a visual artist, so how it looks. I don't know if it's to my practice, but it was amazing.

The mystery that still remains, you know, I don't know, it's like a non-scientist, you think, oh, scientists may, they know exactly what they're doing or, or like you think, oh, economists, like bankers know how they connect.Nobody knows, you know?

Yeah, I agree.Maybe that's where the magic is, right?

Yeah, exactly.That's where the magic comes.

It's interesting how both of you touched on this idea of not knowing as part of the work, as part of the process, how each discovery adds to a larger understanding, even if the full picture is still kind of out of reach.

Mika, do you ever feel that kind of uncertainty in your own work?I'm specifically thinking about your most recent work, which is a departure from video, right?

Now you're making sculptural lampshades that look like elaborate mushroom forests, and you've made them by repurposing waste plastic from detergent bottles.What was the genesis of this?How did this process begin for you?

I mean, this is from one hand pretty new to me because I usually make videos and I make a lot of stuff for the videos.So I make the sets and all that.So it's not that different in terms of the practice.

I decided that now I'm going to like kind of zoom into a material.I wanted to use a material that I have a different kind of relationship with. And I wanted to, all the work explore modes of production in a way, the way things are made.

So I wanted to not necessarily just reflect on that.I wanted to create my own very small, small scale mining operation.

So we kind of mined the streets for, for this, what is like natural resource at this point, which is the plastic and make stuff from it. And, you know, we're doing it because there is no recycling in the US, hardly.

It's a failing system and it doesn't work.It's not, you know, the people that should be doing it is the people that make these stuff.You know, it shouldn't be me, but no, they're not doing it.

I like the metaphorical alchemy in a way in it is that you take something and what it is, it is fossil fuel.It is like ancient life in a way.It is a natural material that is just cannot go back.

So this is material that's traveled from ancient life into fossil fuel, into everyday plastic, right?It's fascinating because it's plastic, unlike water or ice, which can shift between forms, right?

These materials are reaching a kind of an end, like an Anthropocene endpoint, if you will, where consumers just discard it and it becomes waste that can't go back into the ecosystem.But you've turned it into a source of wonder and awe.

Felix, I'm wondering what all of this kind of means to you, what it stirs up in you.

Historically, there's this idea that scientists study the world that is sort of separate from them.So that's like this idea of objectivism, I guess, right?That you can affect the world and it doesn't affect you back, essentially.

I'm not sure if that was ever true, really, but now I think there's a kind of move towards, we've kind of deconstructed the world and understood the elementary particles, like with the help of Sun, Higgs boson being the sort of last piece of the puzzle in the Standard Model.

So now I feel like the task is to sort of put that all together and say, okay, we've understood like breaking it apart, but now we need to understand that we're not separate from the world we're studying.It's affecting us and we're affecting it.

And I think there's sort of deeper kind of environmental consequences for that mindset, right?We've gone from this idea, not even that long ago, is that the world is this thing that we can draw things from and it doesn't affect anything else.

So we can take petrol out of the ground and all these things.

It's kind of similar to what you're saying about it's a very one-sided thing, but you need to acknowledge that you're affecting the world by doing that, and the world is affecting you in the process.

It might be a bit of a lofty idea, but I like to think that condensed matter physics is kind of a, you naturally can't separate yourself from the world.Matter is always on a human scale, in a sense.

You're made of matter, and it is familiar, and there's a reason behind that.So you have to acknowledge that you're part of the system you're studying.You can't really

isolate yourself and pretend you can take stuff from the world without having deeper consequences, I guess.

So Felix, I'm curious how this changes the way that you approach the questions that you're interested in.

Because I was struck earlier, I had assumed both of you started with the idea of making objects and moved towards a process to make those objects, but it sounds like you both begin with questions and a process, and then you let the objects emerge from that, or the insights emerge from that.

You have to be kind of obsessed with doing the day-to-day work, because otherwise, you know, the amount of work you have is a lot more than like a working week.It has to be like your hobby and your job as well.

So the actual doing of it has to be the motivation, I think.So like, if I give an example of something we're thinking about right now, there are these kinds of particles that can exist that aren't individual particles.

They come about through the interactions of other particles.We're even debating now amongst ourselves, if these things are really particles or not, we're not certain about this, but they've got some very cool properties.

But when you say it's a different kind of particle, can you explain how did you make it?And do you mean like the way it's organized?What do you mean by that?

Yeah, this is the thing we're probably the most interested in, in condensed matter.So as like an elementary particle, you have light, when we call it a photon, and a particle is also a wave at the same time.

So light is a wave, but you can describe it as a particle.You can think of it either as waves of light coming out, or like a stream of individual particles.So inside materials, you can have these particles that just couldn't exist by themselves.

So light can exist by itself, but you can't hear the Sun because sound can't travel through a vacuum.But when you have something it can travel through, like a metal say, then sound can travel through it like a wave, and that's the usual description.

But you can also perfectly well describe it as a stream of particles again, and then those things are called phonons rather than photons.

You can't look for phonons at CERN, because in a sense they're just vibrating atoms, but mathematically they're completely equivalent

Everything is a vibration in a way, no?

Yes, you could say that, I suppose.Yeah, that's one neat way to put quantum field theory, I guess.Everything's a vibration.

You know, I think about, in a way, my videos more and more as evoking these kind of vibrations.And it can be like vibrations and like connections in your brain or on your body, like the ASMR-y kind of.

Cause it is on a human scale, like how we, we are that magic.All these things that you're describing are in us. Right.Like they're not something we observe.It is how we're made.And there's like a kind of a fundamental principle in it.

So I don't know, as an artist, I think you often try to map your existence to in one way or another, you know, within these systems.

There's a quote from Alan Watts where he's saying something like, people have this relationship to the world like an apple to a tree.

You think you're separate to it, but really, well, you're breathing in air and then the molecules become part of you, and then you breathe out and you become part of the air.And like,

The apple, it's not really, it's attached to the tree and it's come from the tree and it's like exchanging stuff with the tree.

And you sort of think, well, they're similar, but then when the apple drops off the tree, then you're like, oh, they're totally separate things.But that's a very strange way to look at it really.

And it's also strange to think you're separate to the world.

Right.That's why I also love these things like nails and hair and all that, because it's like, where do you end?And like the world like begins.

But I guess you mentioned how that kind of way of thinking that we're not a separate thing that we observe that we are, you know, part of that.But how does that way of thinking change physics?

In the early 20th century, say, we kind of thought we could isolate systems, study them independently of us, and we were breaking things down into individual particles.

Then in the 50s, 60s, we got complex enough in our calculations that we could start considering lots of things together.I think there's a natural progression as we sort of build things back up, and we stop trying to be reductionist in that sense.

We're instead looking at how things behave collectively, and then that really links up to other stuff like economics or big scale systems that you could study. Like the Nobel Prizes this year have all gone to these AI things.

Two of them were really condensed matter physicists that are doing that, or they were studying condensed matter physics systems that then turned into this modern understanding of AI.

Because really, you're looking at collective behaviours of things, and they don't have to be molecules making liquids, say.It can be information that's combining.

Actually, like you said, Mika, it can be humans who individually don't really know what they're talking about, but collectively the end result is progress.

That's like, yeah, I'm fascinated that you could look at how matter is and then from that movement, like kind of analyzing that movement, then you could conclude how language works or something.

It's amazing that there is like this code in anything, in everything.

Mika, I love that idea of a code that runs through everything.It makes me wonder, do you see that code perhaps as a link between the exploratory work of art making and the proof-seeking work of scientific research?

For our listeners, I think they'd love to understand how you process the similarities and differences between these worlds of art and science.How does what Felix does and how he thinks compare with your own process and your own practice?

I guess it's similar to art in the sense that I got to prove that this is interesting to other artists and viewers.

I mean, I could still do it and it could actually be a great work of art and they just don't get it, which is the same as for an experiment.But I don't know how you prove that a piece works.

You know, I'm working on a new film now and it has all these elements and all these connections.And I work with the collaborators.So we talk a lot about these things and the sense, but it's our way of making sense of the world.

And, you know, it's been a year of trying to make sense of it.And then when you make it, people get a whole other sense from it.Of course, they want to know what your sense is, but hopefully they get their own story from it.

And I don't have to explain to them because for me, that's, a failed piece if I have to explain to them if they don't have an experience watching it.

This has been an amazing conversation.We've explored how the ordinary world holds mystery and magic and we've gone from simple materials to cosmic forces.

So for this last question, I wanted to bring us back to the idea of finding magic in the mundane.

Every day we encounter countless familiar things that pretty much go unnoticed, but your work shows us that some of these objects have stories, have mysteries that we're still beginning to uncover.

Do you see yourselves as discoverers, as folks who are inviting others to view the world with fresh eyes?

I feel like I'm just trying to point out that this subject exists, so it's more like other people have done the showing by and large, and I'm just saying, hey, you should notice that.

But I do think there's quite a, yeah, there's a magic in the mundane, I guess. I think people should appreciate the stuff around them.I was in the desert in America, actually, and I was talking to this magician there who I bumped into.

I didn't know him.And I asked him if he knew this English magician called Derren Brown.He'd heard of him.He said he thought he was the best magician in the world, which was cool.And so he used to have a TV show in England that was very exciting.

And I said, the reason I think this guy is the best magician is because he makes you believe in magic again.

He does these tricks and he sort of says, well, it's based on like psychology and he does kind of like mind tricks on people that makes them behave in strange ways and this kind of thing.And you think, wow, we know so little about our brain.

And of course, you know, we really don't know a lot about our brain.And it's so bizarre because it's, it's our entire existence and that, and you can do all these tricks to it.

But with more time, you start to see that a lot of his tricks he's doing are really just like standard magic tricks, but because he framed it in this way that made it, he made you believe in the magic again.So you sort of fallen for the trick.

I guess I came around to thinking that's kind of what we do in science.When you're young, the world is just magical.Children do just sort of pick up random objects in front of them and find them intriguing.

And then when you get a bit older, you start to think, well, I kind of understand that.I don't need to pick up these random objects and inspect them in detail, because I've got a basic idea of how everything in the world works.

So you kind of lose that sense of magic. But then scientists devote their lives to studying those things that are right in front of you, so they must be seeing something magical again in it.

So I think that's the trick, to try and return to that sense of wonder you had when you were growing up, but now with that understanding you got when you became an adult.So you want to get that, but still find it magical again.

That's really great.I mean, I love that the more you know, the more actually back to being naive you could be, or not really naive, but charmed, you know?

I was also thinking a lot about magic also as a, from a psychological perspective, like also like a pre-verbal state where, you know, this lack of separation between the self and the world.So there's that rapture at some point where

like I think it's like mirror stage or whatever, you know, that you understand that you're separate from the world, you can't affect things.And until then you think that you have this magic thing.

So I like to think about also the way I make the work from that to this pre-verbal, pre kind of separation space, you know, which in a way is magic.

Cause that magic is, is like this belief that you could affect things just with your mind, meaning that you're one with it.

And then to look at it also from the physicist's point of view, which is in a way that kind of magic, which is similar, because again, it's that we are all part of the same system and the same kind of principle and the same kind of movement.

I'm Geoff Chang, and you've been on a journey to the edge of reason. Join us next week when we speak to Hauser & Wirth artist Glenn Ligon and multi-hyphenate artist Solange Knowles to explore how multiplicity drives their work.

If you've enjoyed what you've just heard, like and review us on Apple Podcasts and help spread the word about our series to other listeners like you.

Sign in

Sign in Sign in

Sign in Sign in

Sign in