In our first episode, I noted how we live in unreasonable times, and that it's in times like these that we return to the biggest ideas.Humanism.Individualism.Progress.Inquiry.Reason itself.

All of these ideas are worthy of our attention and our debate.

But perhaps no debates have felt more disorienting, destabilizing, and impassioned than those over the idea of liberty, which raises questions about the rights of individuals, our individual autonomy, and the very nature of what freedom means to us.

To Enlightenment thinkers, liberty was essential.Without it, we would be unable to constitute ourselves as nations of free people. But these thinkers who spoke about liberty then were mostly men.

And some have argued that they defined the liberty in part by those who could not receive it.Slaves.Women.Indigenous people.Colonized peoples.Immigrants.

Over the last three centuries, liberties have been expanded to many of those people at a great cost to human life.Liberty has been a constant battleground.

In this, our final episode, we ask the artist Lorna Simpson and the poet, scholar, and arts leader, Elizabeth Alexander, about the stakes of liberty and freedom and the role that art and artists have to play in these urgent debates.

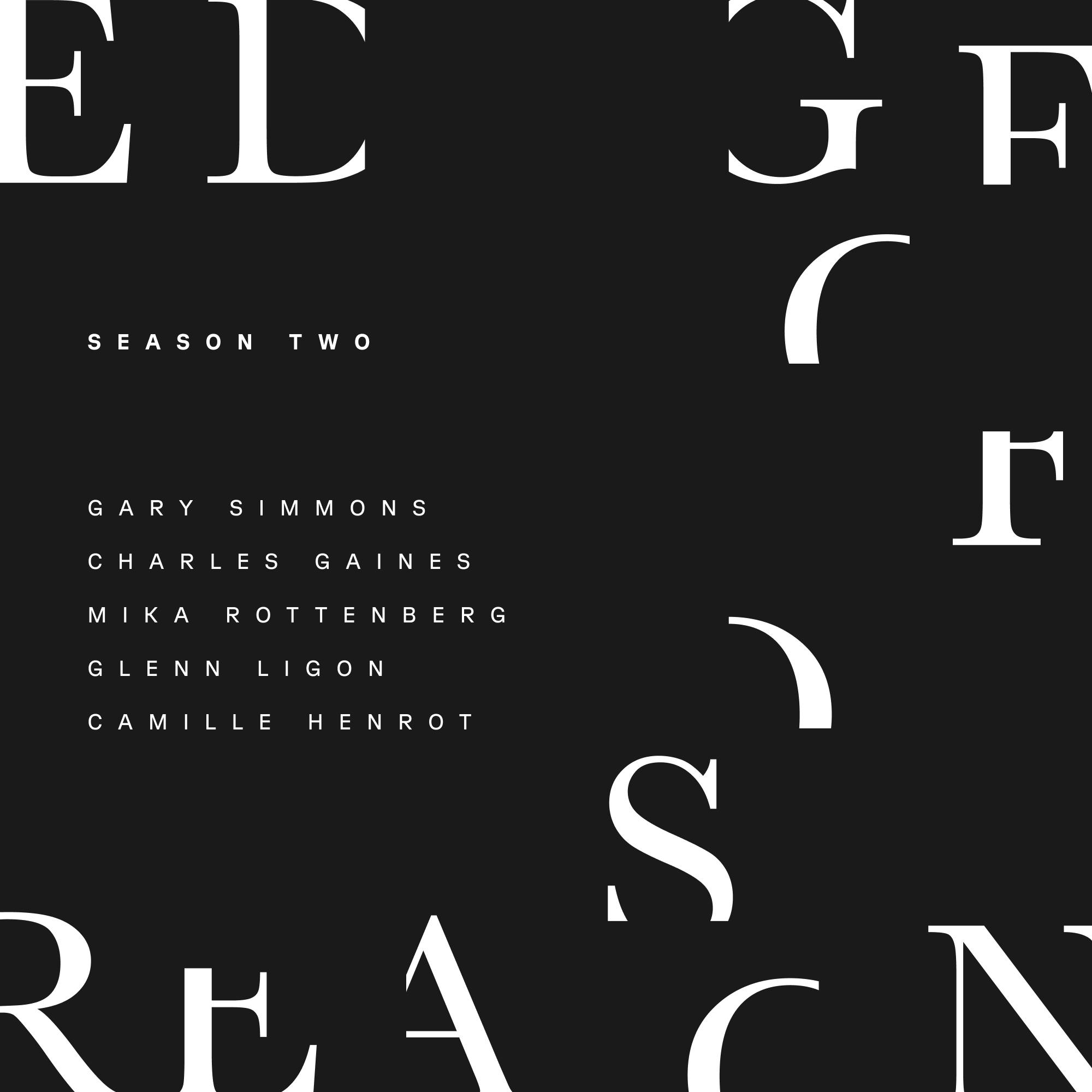

Welcome to Edge of Reason. A limited series podcast produced by Atlantic Rethink, the Atlantic's branded content studio, in partnership with Hauser & Wirth, a global leader in contemporary art.

For the past six weeks, we transcended the boundaries of time and thought, channeling the spirit of the Enlightenment to delve into the obsessions that underpin the work of some of today's leading artists.

This week, we speak to Lorna Simpson, one of the most celebrated artists of our time, whose expansive work across genres began by incorporating images and texts, and has in time come to transform the way we see photography and contemporary art.

And joining us also is Dr. Elizabeth Alexander, a celebrated poet, scholar, and cultural advocate who delivered her poem Praise Song for the Day at President Barack Obama's inauguration, and who has served as the president of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation since 2018.

Her most recent book is The Trayvon Generation. Lerna, I'd like to start with you.You grew up in New York City and you were surrounded by arts and artists.And I'm wondering, what kind of freedom do you think that imbued in you at a young age?

I think I was always, by the attention of my parents, placed in situations where either my creativity or learning things, kind of the amount of different kind of disciplines that I was introduced to were numerous.

you know, from dance to tap dancing and violin and visual arts.And it wasn't about a success or doing well in anything.I think in terms of dance, I thought as a dancer, you learn and you kind of learn from the people around you.

So it was a collaborative. kind of effort.I had a sense of freedom in it because it really was due to my own motivation, my understanding, and my own pursuit.And I could choose at any time not to.I didn't have stage parents in that way.

And many things that they introduced me to, I realized I wasn't interested in. It was the interesting thing, which has to do with autonomy of being able to choose of, oh, this isn't quite right, but this is.

And I think as a young person or as a kind of eight or nine-year-old, that really stuck with me, that I could make those kinds of decisions.It was just as important of the things that I loved doing as it was the things that I chose not to do anymore.

And you were given a camera at a very young age, I understand.

Yes. One winter I was sick with the flu and I kind of collected so many tissue boxes that on the back of them, they said you could, by cutting them out, you would get a Polaroid camera.And I got a camera that was my own.

So I always kind of played with photography or found it as a fascinating, just a camera and kind of understanding analog style, what to do with it and how to work it.

The work that brought you to prominence in the 1980s was photography.And in many of these photographs, the Black women subjects have their backs turned to the camera or their faces turned away.

But then more recently, you've been doing a lot of work with photography and collages in which Black women are actually looking directly into the camera.And it made me wonder,

What have you been trying to convey about power, about the gaze, about freedom in your work, and how have your concerns kind of changed over time?

I don't know if my concerns have changed in so much that the world around me is kind of still circling and we're still dealing with some of the very same issues that I, as a young person, experienced.

But I would say that, I mean, part of my fascination with photography is what we want to project into it.That somehow the subject or the portrait is part of our imagination.

So there's so much that we want to invest in terms of emotional turmoil or reading something in someone's face that is meaningful.And so with those photos from the 80s, it was more of a attempt for me to think about

how a viewer might not be given everything that they want in a photograph.There might be something lacking or missing or doesn't make sense and then to kind of interrogate the image in a different way.

But the work now, I mean, somewhat in the same way because many of the faces or the collages are for ads.So all of the images are constructed.

They are not kind of intimate portrait of someone, but in that way, and in some of the paintings, they are composites of a lot of different faces.

So the thing about knowing someone from a portrait or knowing something about the subject is always a kind of gray area that operates within the work.

Have you worked in so many different kinds of media over the years?You've done paintings, you've done drawings, you've done sculpture, you've done video.And photography seems to kind of be the through line.

The writer Tasia Cole says that freedom is Lorna Simpson's starting point and her permanent theme.So I'm wondering, yeah, you just sort of chuckled there.I'm wondering, do you agree with that?How does that land for you?

I think that's really important for me, personally, kind of starting place.So when I look and read other artists' work and writers, I do think about that.I do think that if they were not brave enough, then we would be deprived of that gift.

So for me, that's just, I guess, even philosophically an important starting place, even in terms of my own work, yes.

Okay, let's bring in Dr. Elizabeth Alexander.You grew up in a household where your family was deeply engaged in civic life.Your mother was a historian.

Your father was the first African-American to serve as a secretary of the army under President Lyndon B. Johnson.Did they imbue you with a love of words and of public service?

Yeah, well, I grew up in a household with a lot of different things.

So certainly the idea of service was very, very important and of being race people and understanding that any educational opportunities we had, any rooms we could be in, we should never be in those rooms alone.

That the only point of being able to have some liberty and some freedom you know, here I'm invoking Toni Morrison, is to free someone else.

So that certainly was something that was always there and a sense of duty that was very, very joyful and a sense of duty that was sometimes irreverent, you know, because, you know.

anybody's people will make them crazy in the midst of, you know, being a part of that community.And that just, again, it was a privilege and no other people or mission to whom it was more beautiful to devote oneself. So there was all of that.

I think that also my mother became a historian actually when I was in graduate school.

So that was not her, though she was a historian in kind of mind construction, my mother was always the one who held the stories, who knew the stories, who was a deep and powerful reader, who put together timelines.

But before she had that training, my mother was also the person who exposed us and me to the visual arts, like Lorna, to dance.Dance was the most serious thing I did besides go to school growing up.

Performing with a company, that was my absolute devotion.And it ordered everything.

I mean, I think that what I learned from that, maybe the most important thing was that you could love something very much and be very, very good at it, but not be good enough at it. to have that be the art form that you would work in.

Loving it and practicing does not make you an artist.Just because I did it six days a week and I loved it and even got paid for it, didn't mean that that's what I was good enough to be able to do.But it did teach me

I really love the dancer Garth Fagan and his dance company.And one of his refrains to his dancers is, discipline is freedom.Discipline is freedom.

So that it is in that practice, in that getting stronger as with athletics, so that you can do an improbable thing in your freedom of movement, right?That you can be free. to really dance, to make shapes.

And so similarly, I think that, you know, what is the woodshed for any other form of art that you might work in.You know, all of the hours and hours and hours and days, weeks, months, years that enables you to be able to make something.

What an extraordinary miracle.And the freedom of making that which comes from within and that you don't even know what it's going to look like when you go in to find it.So that's freedom.

That's freedom, but it is dependent on discipline because I think that the ability to be able to execute on the vision is crucial to what makes it worth doing.

As a mother, you've written about the generation of your children.Your children are the age of my children, of Lorna's daughter as well, and you've called them the Trayvon generation.What do you worry about for them?What are your wishes for them?

it's starting with my children, but you know, Zora is my child and the circles of, you know, that Lorna and I love each other's children, those circles hopefully just go out and out and out and out and out and out so that our care for the ones who we're entrusted with has always got to be much, much, much bigger than, than just those children.

And look, I mean, you know, I, I think that, growing up in a period where racially based and motivated violence is not only increasing, but also visually reproduced over and over and over again.It's the technology of racial violence that has changed.

So what am I worried about?I mean, I'm worried about what happens to a 17-year-old black girl who stands in front of four police officers murdering a man in real time and somehow knows she has to film it.

But the trauma of all of that, I don't know what the recovery is from that trauma. you know, their own sense of vulnerability.

I mean, I think to freedom, you know, with the years of COVID and just that sense that in our bodies, we cannot be at liberty and free to move around and, you know, be wet and messy in the way of young people.I mean, in very literal terms, that our

daughters, our girls, cannot do what they want to do with their bodies.Their bodies are regulated by the state.

and that to sexual partners, that their lives too can change and are profoundly affected by something that I think in our generation, the three of us, we truly believed was a settled matter, that that was a right.

So I think, and then when you put on top of that, all that is plainly happening, you no longer need to have intellectual knowledge of climate change to understand that we are actively in the midst of it.

We know this, but I think that how our young people are experiencing the existentialness of it has created a tremendous generational anxiety.I'm worried about that.

I completely agree.I think also COVID was this moment, particularly for young people, of a kind of undoing. that in watching television and watching all these things, but also the kind of madness that they witnessed every day.

So the thing of being isolated, even in the terms of before the pandemic, kind of was not a relief, was not a kind of, well, everyone is kind of safe in their homes.I think that profoundly the isolation, but also watching, you know, the scapegoating

of people of color during that entire period as well.And George Floyd, of course, was horrifying.So I think it was this thing of coming of age and wondering what kind of world am I occupying and what kind of time, what is this all signaling?

I mean, I think it's the same signals, the same dog whistles, the same kind of tactics from 60 years ago, 70 years ago.

But I think for young people who did grow up seeing Obama, did grow up in terms of their own sense of their own bodies and sexuality in a particular way,

that there's this moment where everything kind of comes to a halt and there's this desire to retreat to a past that is kind of at least 80 years ago.

I think also, what is the role or possibility of art in this time?And I think about, I'm hearing in my head a Robert Hayden poem that I love

called Monet's Water Lilies, and he says, here when the smoke from Selma and Saigon poisons the air like fallout, I come again to see the serene great painting that I love.

And it goes, Monet's Water Lilies, and then he sort of enters into the painting not as solace, it's rather what happens to the self when we enter into the light and space of this particular painting.

And so I think too about Lorna's, I'll call them the big blues, and that those paintings were made in this time of anxiety that we're talking about.And so for me, the experience of being with some of those paintings is,

akin to the Hayden, like the Monet, they were big enough to enter into.So, I mean, I just think this is kind of a fascinating thing.It's like we just keep making and what does that give our young people?

I mean, I believe that that gives our young people profound things and that, of course, we receive back from them.

I am never sure of what people like when I'm making something and kind of its result.

And I mean, for me, many of those paintings are immersive, but they're also very isolating and very somewhat a little foreboding in these kind of environments that are literally fading in the work.

As an artist, it feels very much like I am delivering something, but it's interesting because I feel the action of making it or the process is important for me, but I am continually mystified when the work moves someone.

It moves me or it's sometimes like making work is really hard and you're like, I'm not too sure about this work, but I gave it everything I had.I certainly do find that in the work of other people.

What's so, I think, amazing about when I used to write poems, which I haven't done for a long time, part of how I would know I was done is that it would be a little strange to me.It would become unfamiliar.

I would know that at that point when it became unfamiliar and I didn't quite recognize it, And then it's like, oh, and I really do think it's like, oh, I gave birth and now it's outside my body.And like a like a colt, it can walk when it's born.

I'll have to teach it how to walk.So then and then begins the life of living in the world outside of our control.And, you know, just that, you know, beautiful power of like, off it goes for people to experience.

It seems like during the pandemic, notions of liberty and freedom became a real battleground.And we're still seeing that happening.And so I wanted to get to this question of what happens when the art gets out into the world?

And then you have groups in the name of liberty saying, no, actually, we should be banning these books.We should be preventing people from seeing this artwork.

I can't say it's shocking, but it is good old fascism.We've been here before.And I mean, I was just in Zurich with a show at Hausernworth.Their publishing house is in the store that was operated by Jews who had a bookstore in the 30s.

And they had this whole display in their window about the burning of books in like 1934. And so, you know, like, this is not new.These tactics are not new.

And I think it doesn't make it less horrible, but it certainly really points to a retreat or to a system of fascism that is very well trodden in this world.

And I guess that's what, that's not the loss of freedom, but it's the want to return to a past of horror. It's like a reenactment to me.

I'm wondering about your collages, which you made in large part by taking images from Jet magazine, from Ebony magazine.What are the uses of the past, especially in thinking about questions that might haunt the ideas of liberty and freedom?

I feel in terms of the work that everything is an archive and we speak and travel and communicate in this world of images that are swirling kind of either quote unquote copies or doppelgangers or avatars of the past.

I mean, I think the banning of books now, it's very similar to the burning of books in the 30s.

So I kind of feel like there is so much territory that it's because we designate a particular kind of meaning to particular images from a time that they should only exist there.And I think sometimes with my use of

photography or kind of appropriating images from magazines, it's also this thing that we are living in a world of just images all the time.So the kind of reconsexualization of those things in the present brings them forward to me.

I would hope, or like I can't say that that's always the case, that there isn't a sense of nostalgia that colors it.

But in that the collages are kind of surreal and impossible, and they're based on images that are somewhat very quirky or in and of themselves surreal, that that gives it a kind of different edge.

I was just thinking about some of that work and what I think is so interesting.I mean, first of all, that Ebony and Jet, I mean, I don't think there is any bigger archive of Black people, you know, so like, wow, like just all of that.

But then in the work, what's really interesting is that they're not, those people, right?I mean, it's not like Susan Jones.She becomes something else.

And taking it to early work of yours, I'm thinking about the photograph of your mother pregnant with you. And then other work where there are repeating images where, at least in my experience of looking at it, is it a relative?Is it her?

Is she dressed up?Like, who is the Black lady across time?You know, how are these Black women connected to each other?And you're never certain.It is a really rich and layered experience of looking.

end of being and kind of how people are in the world.

And I would hope to, at least in terms of my imagination, you know, create this other kind of space of the way the figure or a person kind of operates in the world, a kind of different freedom system that is not inherent on permission or possibility.

I think, I've written about this, that, you know, collage is a quintessentially Black art form. because of the ways at the root of black culture, that we are always taking the scraps and making something new.We are always sampling.

My older son has an epic, epic, always added to playlist of song and sample, and sample, and sample, and finding all of the permutations.It's so much fun to think like, ah, they just took that note, Yeah, I know that note.

But then it becomes something new in the new context.I think that that is what comes out of a culture of scraps and making the most extraordinary and beautiful things anew out of those scraps.

And also with regard to freedom, I mean, when I think of even Toni Morrison's work, you know, no one is ever going to give, and this is not a quote of hers, but I got my musings about the characters.They never ask for permission, nor do they wait.

That's right.That's right.For their freedom, for their liberation, for an answer.Mm-hmm.You know, it may start out as questions or problematic, but they do not wait.

Yeah, no, that's right.You know, also, I think as I was thinking, preparing to come into the conversation about liberty and free and freedom, I was like, I don't ever say liberty.

When you started with it, with this enlightenment idea of liberty, you said this, like, it does not include our liberty.So we already, like the model is busted from the beginning.It's not our word, but hey, we can talk to you about freedom.

and the word free and if you just look in also like look in the black musical canon of you know like oh you know oh freedom i wish that i knew how to feel to be free i mean you know all of the ways in which

we use and sing that word free and freedom because that's the word with resonance.I went down an etymological rabbit hole.Liberty has freedom in it, but free has love in its Indo-European root.Isn't that interesting?Again, in a black context,

I think that we already know that liberty is an ironic concept because it didn't include us in the first place.

Or in order for those to have liberty, there were class and vastness of people who had in order for that to be possible.That is right.

For liberty to be there, there had to be folks who didn't have liberty.

Yeah, but we can talk about some freedom.

I love that because liberty is thought of usually within a system, right?Like within a system of politics or a system of laws.Freedom is a little bit more of a feeling.It's a state of mind.

Well, and also I think that it's something that we found when we did not legally have it.Like Langston Hughes's, I return so often to the Negro writer in the Racial Mountain, which is I think 1925.

He says like, you know, we have to say what we have to say.We have to be free to say what we have to say.If white people are pleased, fine.If white people are not pleased, that's fine.If black people are pleased, fine.If black people are not pleased.

So in the middle of the Harlem Renaissance, he's saying, Guess what?We don't agree on everything and you may not like what I make.But we stand atop the racial mountain, and he says, the Tom Tom sings and the Tom Tom cries.

We stand atop the racial mountain free within ourselves.To take it forward to where we started, our bodies are constrained.Our movement is constrained.Our futures feel constrained. what does it mean to be free within ourselves?

And that can be answered so many ways, not always ways that feel wonderful.

I want to go back to an idea that you brought up, Lorna, of being able to create within your work a kind of a space to be able to imagine something that's different.

What are our possibilities if artists are able to have their full liberties to be able to pursue these notions?

I kind of feel like, again, you never ask permission.And the moment that freedom or one's liberty becomes contingent on a permission or you find yourself in a trap because it will never be given.I mean, why should it?

I think the status quo of kind of keeping everyone in line or in the idea that it is impossible and it is forbidden and we're gonna make your life horrible.

But I think the desire to create is much stronger than that, but also the kind of the human condition and people's desire to be themselves to kind of create a space to live or to be has always been with us.

And so, you know, I think in these many years now as an artist, I think it is just something continually that we have to fight for, that it's that sense that you can, although everything around you says that you cannot, is something that one has to learn how to deal with, but more importantly, ignore.

And it's difficult, I'm not saying that that's easy and I'm not saying that people haven't lost their lives in doing that, which is like Elizabeth was saying, which allows me and her and you to sit here and for us to speak about this.

But I think the more and more I see this, you know, it returns with the erosion of small rights and small things and targeting groups and then the targets get larger and larger and larger. And so all those same patterns continue.

But I think certainly for the generation that are young people in their 20s, I am very heartened because they understand who they are.They have lived their lives in a particular way that embraced

the sense of freedom, and I do not think they're ready to give it up.I think it will be a battle.I think that it will be difficult, but I think they are up for the challenge just like many other generations before them.

The concept of liberty was penned by privileged minds at a time when many communities weren't afforded any rights at all.

So, as we wrap up our series on the principles of the Enlightenment, it's crucial that we recognize the chasm between the ideals and their application.

This series exists because re-examining these concepts in the context of our modern world is not just enlightening, it's essential.

We have to continue to unpack, to question, and to reframe these principles with an expansiveness and a consciousness they've historically lacked.And there's still a long way to go.

So, as you journey forward, please take with you the lessons and conversations we've shared, reflecting on how we can shape a future that truly embodies liberty and pushes these ideas to the very edge of reason.I'm Geoff Chang.

Sign in

Sign in Sign in

Sign in Sign in

Sign in