In a world that often accepts surface-level answers, the spirit of inquiry beckons us to search for deeper truths.

It's not just about asking questions, it's about an unquenchable thirst to understand, to dig beyond the obvious, to challenge what we think we know.Inquiry is the compass that guides us through the complexities of our times.

In our era of overwhelming information and rapid transformation, museums emerge as powerful spaces of inquiry.

There, amidst curated artifacts and art, we're reminded that it's not merely about finding answers, it's about asking questions of the questions themselves, exploring the intersections of technology with human experience, and understanding how our surroundings mold our introspection.

Such inquiries push us to perceive not just what lies before our eyes, but also to grapple with the deeper whys and hows of our understanding.In this episode, artist Pipilotti Rist and the curator Anna Katz discuss their own processes of inquiry.

What drives it and why?And where does the spirit of inquiry take them?Welcome to Edge of Reason.

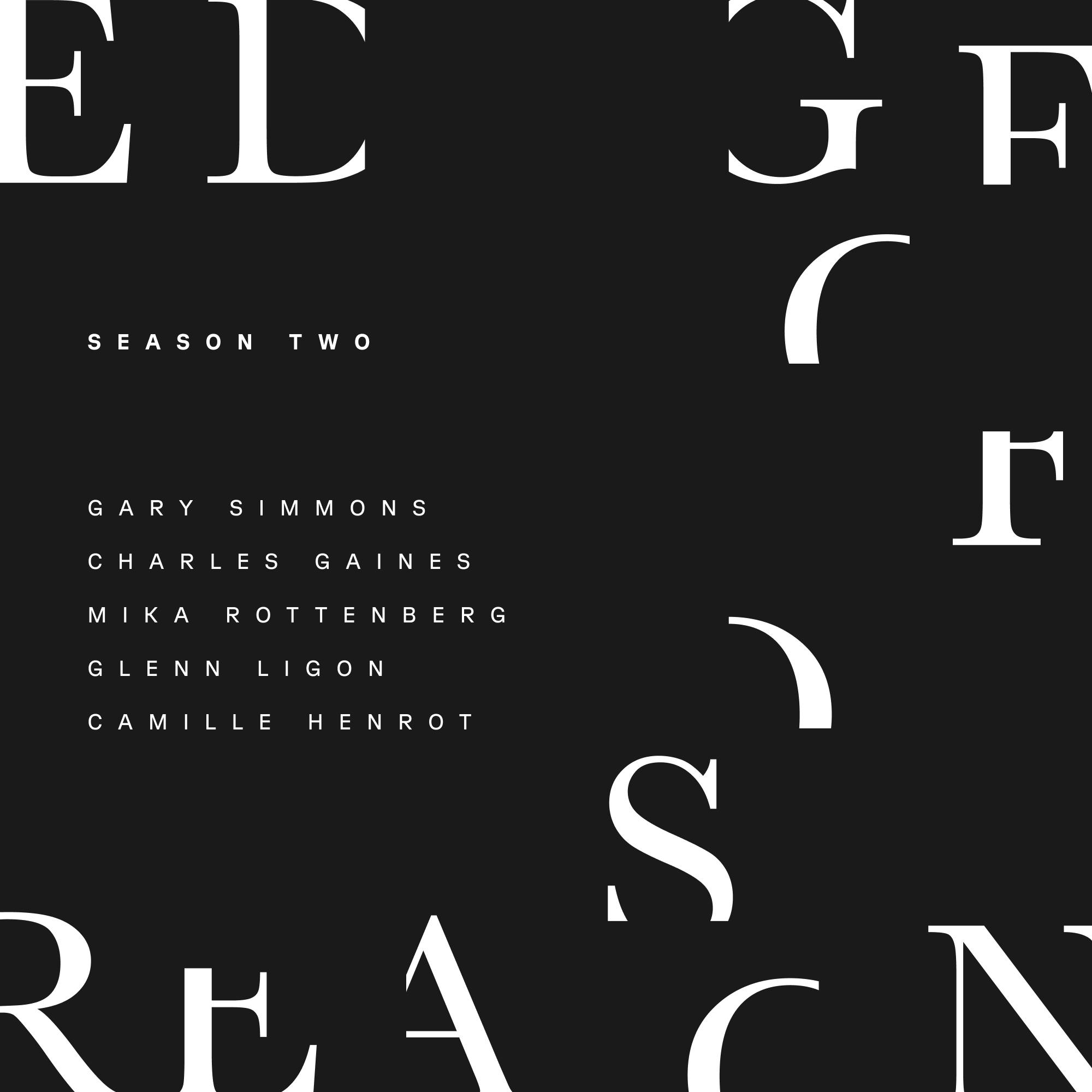

a new limited series podcast produced by Atlantic Rethink, the Atlantic's branded content studio, in partnership with Hauser & Wirth, a global leader in contemporary art.

Each week, we'll transcend the boundaries of time and thought, channeling the spirit of the Enlightenment to delve into the obsessions that underpin the work of some of today's leading artists.

This week, we're speaking with Tipilati Rist, the Swiss artist who has been a global trailblazer in video art, and whose immersive video installations, grand-scale projections, and digital transformations beckon audiences into a deeper exploration and introspection of the human psyche and behavior.

And joining us also is Anna Katz, one of the art world's leading curators and the driving force behind the first West Coast survey of Pippolati's work at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles.Big heartedness, be my neighbor.

Pippolati, I wanted to start with you.You've been such a pioneer in video art.When you began making work in the 1980s, you were interested in music and in dancing, and you were interested in people dancing together. What attracted you to that?

I wanted to prepare rooms with colored lights, moving lights, in that time it was Super 8 and slides, that people get into another state. And I didn't treat myself as an artist in that moment.That only came later.

I more thought of being a service person to make people feel at ease and going to other spiritual levels.Many music expressions have that ability to have a shamanic vision or to come to truth beyond the rational thinking.We are so isolated as humans

And in the end, maybe every cultural expression is a deep wish to understand the others, to overcome the loneliness.And it's a proposition, how you see, feel, hear, and then the other can mirror herself in it or not.

And that's the only way that we can understand and come closer, isn't it?

I'm wondering, when you make your work these days and when you're creating these spaces, what are the kinds of questions that are occupying you?What are you trying to answer and what are you trying to bring your audiences into?

If people take their legs and go to the museum, go to such a place, then we want to welcome them with their whole body, not only intellectual, what they also could see on their screen or phone at home.What is the difference when they come?

What can we add? And one of the important things is the body posture.So you perceive differently if you lay down, relax, or if you take off the shoes.

That's a thing that when people come together, why not make a mood that you pay attention to your other around you?

So your art in drawing people in also reveals this deep curiosity about people.How do you think about inquiry in your art and your artistic practice?

maybe the biggest incentive for inquiry is that we do not understand the other and that we have a brain that is beyond our imagination, so complex.We have a brain, a flash machine that fires billions of synapses

so that we can now understand each other through these electromagnetic waves in sound or in picture, that our senses are processing this.

And we cannot understand it, and we have a deep wish to do, to understand, to realize, and to feel that we are in the same shit.

Okay, so let's bring in Anna Katz now.Anna, you've curated some of the most important artists of our time at the MoCA, but for our listeners, what does that mean exactly?What do you do as a curator?

The work of a museum curator is different maybe than the work of an independent curator.

There are many kinds of curators in the world, but the work of a museum curator has a few essential functions, one of which is to organize exhibitions, organize special exhibitions, and to make catalogs that accompany those exhibitions.

Those exhibitions in a contemporary art museum might have objects that we consider historical in the context of contemporary art, so artworks from the 1940s, 50s, 60s, or it might be work that I've commissioned an artist to make, that I've invited an artist to make, or provided the space for an artist to make, or the funds for an artist to make.

Like in the case of our work with Pippolati, she made a massive new multi-channel work for our exhibition that we did together alongside the presentation of 35 years of previous work.

Tell us a little bit about what the meat of the work was about.

The meat of the work is making art history public, making it an enterprise, a way of looking, a way of seeing, a way of thinking, a way of comporting, a way of interacting, and a way, again, of understanding history in our present moment, available, open, accessible, interpretable to a public audience.

So in the case of our work with Pippolati, some of that has really practical implications, right?Like where are we gonna put this artwork in a way that people can move through the space?

And it's my job to be kind of like the team leader for my team at the museum and my team at the museum's exhibition production and registration, it's education, it's the retail department, it's being kind of the hub of that wheel and the primary interlocutor and interface with the artist.

But sometimes making it public also means like writing exhibition didactics.

How can I explain in 250 words what it is that Pippolati's work has done over the past 35 years to transform our understanding of what video art can be, what feminist art can look like, what pleasure can do and mean in the context of art or discourse, thought or progress.

But very, very slowly, leaving these kinds of breadcrumbs, hopefully, for audiences, curators, historians in the future.

You're trying to imagine 20, 50, 100 years from now, what will people want to know about 2023 and what curators, artists, scholars were thinking about what was most important, most significant, most interesting art of our time.

You're literally curating current history for the future in that way.

looking back into the 70s, the 60s, the 50s, and saying like, oh gosh, we missed that before.We need that now.We can't tell a story of the present moment without having had that object, that movement that was previous to us.

So it moves every which direction, but the little hope is that it's just a teeny tiny little clue.The gestures are small, all things considered.

I'm wondering if we can take it all the way back to the Enlightenment now, which was a period in which the museum was received as a brand new idea, a social innovation.Why do we have museums?And how did they serve as places of inquiry?

Yeah, in the context of the Enlightenment, we have museums because we believe that the king's riches actually should belong to the public.

you know, in the case of France and the French Revolution, that the royal collection of art actually should belong to the people and be open to the people to be put on view in the Louvre so everyone can come see it.

We have museums for lots of different reasons, and they're not all in the public interest.Some of them have to do with private interests.Some of them have to do with narratives of colony and conquest. of imperialism and theft and power.

But some of them within that, or in tension with that, or maybe total collusion with that, depends.Some of them have to do with making spaces where people can gather.We have museums for the reasons that we have libraries.That is,

to ensure that we are recording the cultural production of our time and of history, and that its meaning, that its longevity, that the function of the museum as a storehouse, that its function of preservation, its commitment to perpetuity,

will bear out, that it will make good on itself.

But it can be questioned.In the last couple of years, it's clear it cannot be a fair, objective selection.It's always people who define what comes in the museum have a strong position and I'm very welcoming that in the recent years this was steered.

Yeah, to put a finer point on it, if we're going to compare it to libraries, we know right now that there's a big sort of uproar about books that are in libraries and should books be removed from libraries.

And so the sort of broader question I wanted to get at here is, what are the stakes of the work that you all are doing in the museum and the work that goes into the museums?

for future generations of people who are launching their own inquiry into how they should be creating society?And that's a question for both of you.

Well, one thing I would say maybe just to back up a little bit or to tag onto what Pippolati was saying is that I think most of us who work in the museum are extremely skeptical of the institution of the museum and spend most of our time trying to challenge what counts as art, who counts as an artist, what counts as a museum exhibition, what's good for the museum, who belongs in a museum, that it is not taken as a neutral given in any sense, in any political or ethical sense.

and that most of the artists that we tend to work with are also invested in that kind of inquiry, in that kind of investigation.

How can we push this, rethink this, challenge this, and often to the ends of, of course, greater inclusivity, more diversity, a less hegemonic, monolithic understanding of history, culture, and society.So the stakes have to do

with the stakes of any way that we record history, any way we record what counts, what is good, what is valuable, what is significant, what is meaningful, who can recognize themselves here, whose stories are being told by whom and when, whose stories are being preserved by whom under what conditions.

I did manage to be a bit out of this discussion because my works only function when you give them electricity and then when you unplug them, they are in a way up in air.

So it's hard to store or to collect or if you don't feed them, I would call them like having a horse or an animal. If you don't take care, then they die.

Well, at the same time, your work is very much about the present.It's about bringing together people in a space to begin journeys of inquiry.How do you go about that process?And what goes into your thinking about how you make these spaces?

In that point, I agreed heavily with Anna that a museum room can be a collective room where unknown people meet.And in that moment, they are a group.Considering my

material, which is electronic, technical, projectors, players, all these stuff that many people could also view at home.And if they bring their body, then

really offer them this possibility that they have experiences they cannot have alone in conversation with their plastic screen, but only something that they can experience together in that room.

Maybe, of course, there are many other examples, like cinema has also this magic.What happens if people sit together?But it's a bit more authoritarian.They have to look in one direction, with a beginning and the end.

Whereas in our exhibition, we never know how long they stay, and the things work in loops. It's a choreography that's also one part the curator was very informal to.

But it has a free, kind of a freer way to approach the works, but has some connections with cinema and concerts.

I think maybe a good example of how this works for you would be the set of works that you call The Apartment, which is, in fact, a number of discrete domestic tableau.So there's a couch and end tables and a projection on the couch of waves of water.

And then pixel mapped exactly to the form of the couch.Exactly, which is a kind of technological feat, but looks really easy once or looks really simple.

Once you're in the room, and there's a fireplace that glows, and there's a picture on the wall, a 17th century Italian painting that also has a projection on it and a spinning table.So it's this, it's a recreation of a kind of apartment.

And the idea is that we're behind someone's eyelid, more or less, right?That we're in someone's inner life, someone's inner apartment.

But one of the things that Pippa Lahti does to make this feel like a living room and to put the viewer at ease is she fills this space with little tiny knickknacks.

books that she's used and figurines and toys and lamps and pictures her old boyfriend drew and all the kinds of little objects that you might have like on your bookshelf. you know, all the kinds of objects that you might have in your home.

And the kind of thing that when you go into someone's house is how you get to know them and also how you get to know that they're like a whole person, right?

If you go into someone's house and they don't have any of that stuff, what you say about it is, it was like a museum.And what you mean by that is I clenched I was uncomfortable.Right?Like what you mean by that is I was afraid, you know, to, to relax.

And these are all, I doubt that if you asked most people who walk through the installation of Pippi's that gets called the apartment, are there lots of little toys and figurines?I doubt that most people would say yes.

I don't think that they're ignored it or I think that it just I think they're just felt and I think that actually what that means and something that I'm really interested in is about decoration and decorative objects which the museum and the institution of art

has dismissed soundly for really hundreds of years since the invention of so-called high or fine art in the European and North American tradition around the time of the Renaissance, when there was a division between what was considered intellectual and therefore high and fine, and what was considered craft and material-based.

This division was drawn along gender lines and along racial and ethnic lines.

So really, for hundreds of years, the decorative has been denigrated as everything that is kitschy and lowly, much worse than secondary, and opposed, again, to higher fine art.

But Pippi's work has an interesting, if kind of tangential, embrace of the decorative for these purposes, because it humanizes the spaces of our lives, right, across time and across place.But you made this great exhibition.What was the title?

The title is With Pleasure, Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972 to 1985.Really, it could have been called Pattern and Decoration, which is the name of an art movement that emerged in the 1970s in New York, in LA,

and in between, and is a kind of example maybe to go back to your earlier questions, Jeff, about what a museum can do or what the stakes are.

The stakes are not dramatic, but with a show like this one that I did that Pippi is referring to and that I've been referring to, that we presented at MOCA in 2019,

a show that re-examined a long-dismissed, mostly ignored art historical movement that was really galvanized by feminist art history, by the development of feminist art historical methods in the 1970s, and a movement that embraced all that the artists had been told was

lowly and impure, so needlepoint and quilting and patchwork and fabric design and beadwork and mosaic, everything that, again, in art history has been associated with the work of women and the work of so-called primitive others.

With a show like this, the greatest, most ambitious claim is that so long as we dismiss the decorative, we're consigning ourselves to denigrating the creative, intellectual achievements of women and non-European makers of history.

we've been talking about how the museum has actually limited space-making, if you will.It sounds to me, Pippa Lati, as we're thinking about how you started, right?You're in these sweaty clubs, gallery spaces and that kind of thing.And it seems as if

One of the things that you're doing even now with your immersive installations like Pixel Forest is being able to create that same sort of community space and breaking down these boundaries around the museum, making that a space that is available to people.

But I also wanted to ask about technology, Pippa Lahti, because technology has obviously really changed dramatically since the 1980s. Oh God, yes!You know, is technology something that's freeing but also restricting as well?

The idea of the pixel forest came to me when I went with my friend Kaori Kuwabara, a light designer, to a 3D location where we had goggles, where we can go into a 3D room. but I felt more isolated.

There was a room, that's true, very realistic, but I felt so isolated.And I asked her, can't we do pixel in the room and then we walk together between the pixels?

But this has another effect on people when they walk through and how the image is then put in this addressed pixel.So every pixel in the room knows exactly where it is.

Even it looks organic and the distances between the pixel look chaotic, which is not true. just we wanted not to make it geometrical looking.

And we should describe this.You literally make the pixels into physical things and you hang them, yeah?

Yeah.They are hanged and then Kaori knows on her computer where which pixel is because she knows the distances.She knows where all the strands are hanging.

Then we put in the image, and she has programmed that the pixel in the image there will go in that.Actually, it's the same thing as we have in every screen.Every pixel on the screen knows

which number it is and what they have to play in a certain rhythm to let us feel that we see actually a fata morgana of a picture.

And you were talking a little bit earlier about how screens isolate us in so many ways.Talk a little bit about how the pixel force de-isolates people, how drawing them into this space actually brings them back together.

Now the effect of the pixel forest is beyond my understanding.I got now a letter from a psychiatrist that she did send her heavy depressed patients there.So there's one in Zurich that is permanent now.And this

patient said that since a year she had the first premonition of joy.And now she has from the doctor a prescription to go there every week.So, and what it makes us people go there, just today one, a waiter said, whenever he's stressed, he goes there.

And why exactly is really hard for me to tell, but people feel like they are understood, and they feel like as we would walk in their brain, and as we would walk together in a brain.That's what they say.

You've literally taken them on a journey of inquiry into themselves that ends up with healing.

That's the best that can come because in the moment the artwork is finished, so the artist in a way could die.And it's only important what's happening for if it has a sense or a meaning, a calming, comforting, spirit-opening effect.

How do you foresee your work being experienced 50 years from now, 100 years from now?

I think that if there is a deeper meaning that has a general meaning for other humans too, and humans I consider as animals, I consider as plants with no roots, if they then get something for them, I think the technique is secondary.

It's like a music piece from 500 years.The melody stays, but you play it also on a new violin.So I'm very not dogmatic there.

thinking about your question to Pippalati, I suspect that part of what viewers will see, and this is a moment of deep exploration of what is relatively a new medium, the medium of video and the medium of the handheld video camera.

In Pippalati, they'll see this interest in video, not as a medium of mass media or surveillance technology, but a medium that has as much capacity to show us what's inside of ourselves, what we see when our eyes are closed.

Thank you both so much for being here. I'm Geoff Chang, and you've been on a journey to the edge of reason.

Join us next week when we speak with the artist, Lorna Simpson, and the poet and arts leader, Elizabeth Alexander, to explore the meaning of liberty.

If you've enjoyed what you've just heard, like and review on Apple Podcasts, and help spread the word about our series to other listeners like you.

Sign in

Sign in Sign in

Sign in Sign in

Sign in